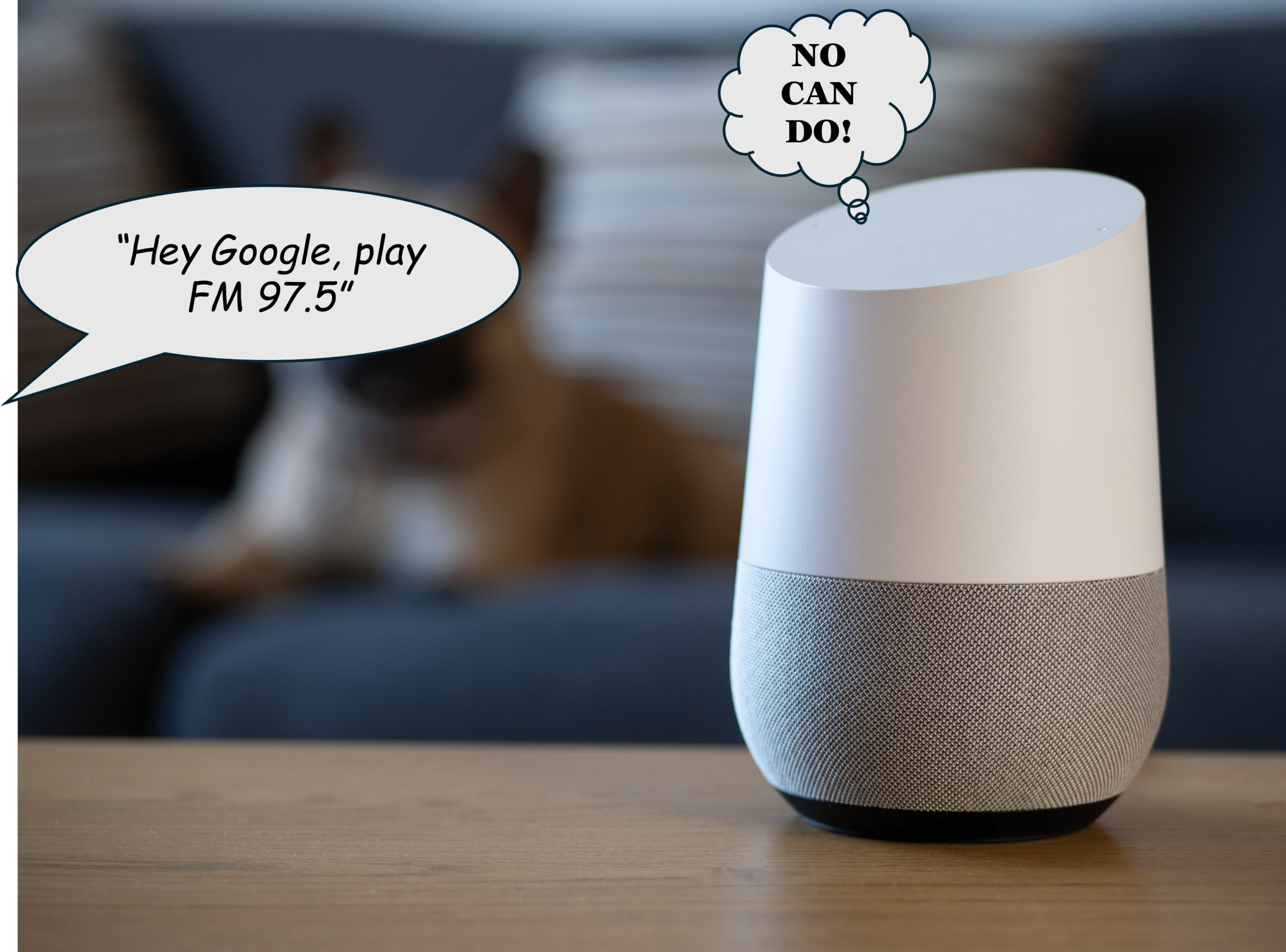

I’m not sure why it required a futurist from Australia to inform us radio streaming on millions of Google Home devices was down for weeks. That’s the story that was shockingly told by James Cridland’s wonderful “Radioville” newsletter over the weekend. If today’s JacoBLOG headline got your attention because you hadn’t heard about this serious software snafu, you’re in a for a wild ride to start a new week.

As James explained it, Google evidently rolled out a firmware update a month or so ago. One of the unforeseen effects of this tech entanglement was it disabled the device’s ability to stream radio in a common format. Familiar commands to Google Home (and Next system) culminated in radio silence. James reports that many stations who discovered this flaw assumed the problem was internal, rather than systemic. In fact, it was a global glitch, and apparently it was no easy task contacting Google, much less imploring them to patch up the error and get everyone streaming again.

James Cridland | Photographer: Tor Erik Schrøder

Cridland suggested that radio companies working together would have been more likely to have convinced Google to institute a fix. Apparently, many broadcasters were hesitant to squawk out of fear of pissing off Google. As James reminds us, imagine what a similar debacle would have meant to American radio stations and their streaming numbers.

It’s a little sketchy about precisely when this happened. Online, some say it may have been as long ago as February. But then I ran into a Reddit exchange between a quizzical listener and KEXP/Seattle that took place at the beginning of May.

So, let’s put this in perspective, especially for American broadcasters.

First, Google Home is a distant second in the smart speaker race, considerably behind the Amazon Alexa platform, so the damage to U.S. radio was far less likely for stations whose call letters begin with W or K. Still, when approximately one-fifth of your audience who owns one of these devices cannot access your stream – during the heart of the spring rating book – it’s a problem.

Second, there is strength in numbers, as James points out. But it also helps to institute the help of the “big dogs,” especially when there’s a serious problem brewing with big tech companies like Apple and Google. I’ve seen the NAB successfully jump into action in similar situations. But they can’t help if they don’t know. It’s also a reminder about broadcast radio’s lack of yank and respect in the world of media and technology.

Third, why did it take so long for this problem to surface, as the word got around about this system-wide Google problem? When a radio station blips off the air, most programmers know about the outage in minutes. But when the stream goes down, it get take days before anyone in authority is informed. Often, it’s a listener who lets the station know about the problem. In the case of an issue with the station app, it usually takes even longer. And a smart speaker screwup? Who knows when the station finally figures it out?

What’s the root cause of this problem? Too many programmers, by and large, don’t place a high enough priority on their digital assets, still treated as secondary to the broadcast signal. Not being aware of a digital glitch is excusable. But if the problem is with the over-the-air platform, it’s inexcusable.

Of course, all this is exacerbated by too many PDs in the U.S. doing multiple jobs for more than one station. The syndrome is actually called “dual hatting,” becoming more common in business and government. (Note that Secretary of State Marco Rubio is currently wearing 4 “hats.”) Risk managers, as you might imagine, warn against this practice getting out of control to the detriment of the organization. In broadcast radio, even casual observers and listeners can detect the problems stemming from the lack of attention to detail.

Of course, all this is exacerbated by too many PDs in the U.S. doing multiple jobs for more than one station. The syndrome is actually called “dual hatting,” becoming more common in business and government. (Note that Secretary of State Marco Rubio is currently wearing 4 “hats.”) Risk managers, as you might imagine, warn against this practice getting out of control to the detriment of the organization. In broadcast radio, even casual observers and listeners can detect the problems stemming from the lack of attention to detail.

Those in leadership positions in the industry should strongly consider instituting a “belt and suspenders” policy around the station’s content platforms. That translates to a daily quick check of the various outlets, including the station’s stream on a computer, the mobile app(s), both smart speaker platforms, Apple CarPlay and Android Auto, and on smart TVs and systems like Sonos. Other sources might include a YouTube channel and Twitch. What am I missing? Add them to the list.

I would also designate one day a week when the programmer and/or head of content monitors the station via the stream – all day and on multiple sources. Why not track these basic performance benchmarks over time, if nothing else but to note the most reliable and least reliable platforms companies offer.

Complicated? Cumbersome? Tedious? I’ll give you that, but they’re essential in this environment.

When audiences have so much choice, your station can ill afford to have a breakdown. They’ll simply go elsewhere. And for advertisers, receiving exposure on all the promised platforms is a tacit expectation that goes along with the decision to use a brand for marketing and advertising.

Digital provides radio broadcasters with added opportunities to be heard – and seen. But with greater exposure comes greater responsibility to keep it all working and running smoothly. It is simply not enough to buy a mobile app, launch a podcast, or start up metadata messaging on car dashboards. These assets all need to be monitored and managed, as well as improved and updated over time. You simply cannot check off the boxes.

not enough to buy a mobile app, launch a podcast, or start up metadata messaging on car dashboards. These assets all need to be monitored and managed, as well as improved and updated over time. You simply cannot check off the boxes.

To get serious about digital (and the revenue that can come with it), it means a commitment to consistency and quality. As too many broadcasters have learned the hard way in recent years, mailing digital in is a recipe for disaster.

Situations similar to the one described by James Cridland are warning shots – cautionary tales to be heeded so there’s not a next time.

Or a last time.

Subscribe to James Cridland’s “Radioville” newsletter here. – FJ

Originally published by Jacobs Media