An industry milestone occurred earlier this week when HD Radio celebrated its 15th birthday – a “glass half empty / glass half full” technology loaded with promise that has either been a major disappointment or a technical breakthrough for the radio broadcasting industry – depending on how you look at it. The story was covered by a number of industry trades, including Inside Radio’s “As HD Radio Turns 15, Industry Looks Back – And Ahead.”

An industry milestone occurred earlier this week when HD Radio celebrated its 15th birthday – a “glass half empty / glass half full” technology loaded with promise that has either been a major disappointment or a technical breakthrough for the radio broadcasting industry – depending on how you look at it. The story was covered by a number of industry trades, including Inside Radio’s “As HD Radio Turns 15, Industry Looks Back – And Ahead.”

The history on HD Radio is…well, checkered. Back in 2006, broadcast radio was beginning to feel some real competitive heat from outside the industry. Satellite radio was beginning its assault, adding Howard Stern to the Sirius lineup. To say it was a shot across the bow was an understatement.

Add to that, Pandora was generating lots of excitement on the streaming front as more and more consumers discovered its music genome, a sort of algorithm that melded your music taste in a unique way. And in the same year, a newcomer called Spotify debuted. Suffice it to say, it was a period when there was lots of buzz. Unfortunately, little to none of it was coming radio’s way.

HD Radio became the solution – a way for broadcast radio’s tightly programmed formats to have “hidden channels” that could be used to counter just about anything. Many at the time dreamed of a new broadcast model with perhaps twice as many formats as before.

Of course, this cut both ways. Radio companies could innovate exciting new formats that could match anything Sirius or XM were programming. But in the process, incumbent stations could be eroded and even mortally wounded by an HD-2 station programming something more niche.

Of course, this cut both ways. Radio companies could innovate exciting new formats that could match anything Sirius or XM were programming. But in the process, incumbent stations could be eroded and even mortally wounded by an HD-2 station programming something more niche.

That dilemma turned into a controversy. And the powers-that-be, not excited about self-inflicted wounds, came up with a novel solution: a “draft” in most markets where companies would be able to declare each of their station’s HD-2 formats, with the group having veto power over any option that appeared to be threatening.

I was able to surreptitiously sit in one of these HD Radio market drafts, and I was able to witness the process. I don’t remember all the particulars and rules, but I do recall that draft order was dictated by the most recent ratings books descending 12+ shares. So, the #1 station in town got to make their pick first, with discussions from the group following each choice over a very crowded conference call.

The draft worked – sort of. It effectively protected the most successful stations in the market. If you were the top-rated Soft AC, you’d be able to pre-empt someone else choosing a similarly programed HD-2 newcomer.

Of course, the unintended consequence of the draft was programming blandness. Because anything that might have had a hint of being innovative, clever, and disruptive ended up getting quashed, most of the new HD entrants were either variations on the tried-and-true themes or were predictably unimpactful.

The other fail with this initial foray into firing up new channels was that most radio companies took a wait-and-see posture on programming, staffing, and marketing them. At the time, there were relatively few HD Radios in circulation. iBiquity – the company that launched HD Radio in the U.S. – initially had a strategy to try to sell these radios to consumers – a piece of gear like a TV or stereo system.

(I still have one of those old Boston Acoustics models on my nightstand, and still see them in radio station offices to this day.)

(I still have one of those old Boston Acoustics models on my nightstand, and still see them in radio station offices to this day.)

But that plan proved to be problematic. While many stations jumped on board to give HD Radios away, sales of these units flagged. And broadcasters began to get discouraged by their lack of market penetration.

Of course, PDs were not incentivized on their HD-2 channels. More often than not, neither were salespeople. And we know how they think. You sell what you’re commissioned on – period. Everything else gets ignored.

Broadcasters themselves couldn’t agree on what worked – and what didn’t. Some hated the name “HD Radio.” There were disagreements about how HD-2s were listed and promoted. Some argued for numbered channels; others liked the idea of the master station owning the brand (WDRV HD-2). Suffice it to say, there were too many issues, too many opinions, and not enough resources behind the technology to make it part of the audio mainstream.

Ultimately, new and highly desirable content drives new technologies like HD Radio. And for the most part, it didn’t exist. When you think back to the growth of FM radio in the ’70s, it was largely driven by adventuresome programming heard on rock stations, as well as quality audio exemplified by classical and “beautiful music” stations. Great radio drove consumer demand for and sales of “FM converters,” and ultimately, automakers included the FM band as standard alongside AM radio in every car that rolled off the assembly lines.

But there were efforts made on the content side. Some companies – and stations – committed to HD-2s. Dan Mason (a former programmer) who ran CBS Radio at the time was a fierce advocate for the technology and the programming possibilities. Many of his stations tried myriad content experiments and approaches.

Tom Bender, who managed Greater Media’s Detroit cluster, put considerable resources into RIFF 2, an HD-2 that specialized in new rock, complete with talent, production, and imaging. With all those auto execs living in Metro Detroit, the strategy was to give them something to listen to and talk about. But these efforts turned out to be too few and far between.

Tom Bender, who managed Greater Media’s Detroit cluster, put considerable resources into RIFF 2, an HD-2 that specialized in new rock, complete with talent, production, and imaging. With all those auto execs living in Metro Detroit, the strategy was to give them something to listen to and talk about. But these efforts turned out to be too few and far between.

There were also disconnects at many levels. While BMW turned out to be an early adopter, broadcasters got discouraged when they walked into a car dealership, where too often no one was familiar with the technology. Similarly, a visit to a Best Buy or a Circuit City often yielded the same shrugs. And there was often little to no signage for these new radios.

And at a time when satellite radio was firing on all cylinders and Apple was heavily marketing its amazing iPod (and later, the iPhone), HD Radio’s advertising program was basically limited to tapping into the commercial inventory of broadcast radio stations across the country.

Describing the technology and why it mattered turned out to be a tall order for what was then the HD Radio Alliance. The chicken-egg-of-it often came down to a lack of HD-2 and HD-3 stations in many markets, negating the “hidden stations” benefit.

Our company was involved on both the consulting and later the creation of some of the messaging and production. It proved to be a daunting challenge for us, and other pros who worked on this project, especially as many broadcasters had moved on long ago.

Perhaps the smartest move made by iBiquity, and later DTS and now Xperi was a refocus on the automotive sector. HD Radio became more present in car industry than in broadcast radio circles as more and more OEMs – car manufacturers – adopted the technology.

Perhaps the smartest move made by iBiquity, and later DTS and now Xperi was a refocus on the automotive sector. HD Radio became more present in car industry than in broadcast radio circles as more and more OEMs – car manufacturers – adopted the technology.

iBiquity had presence in suburban Detroit, where they could engage with the auto industry, and worked hard to remain visible and vital at the Consumer Electronics Show. To this day, just about the only “radio” you see at CES is Xperi and HD Radio.

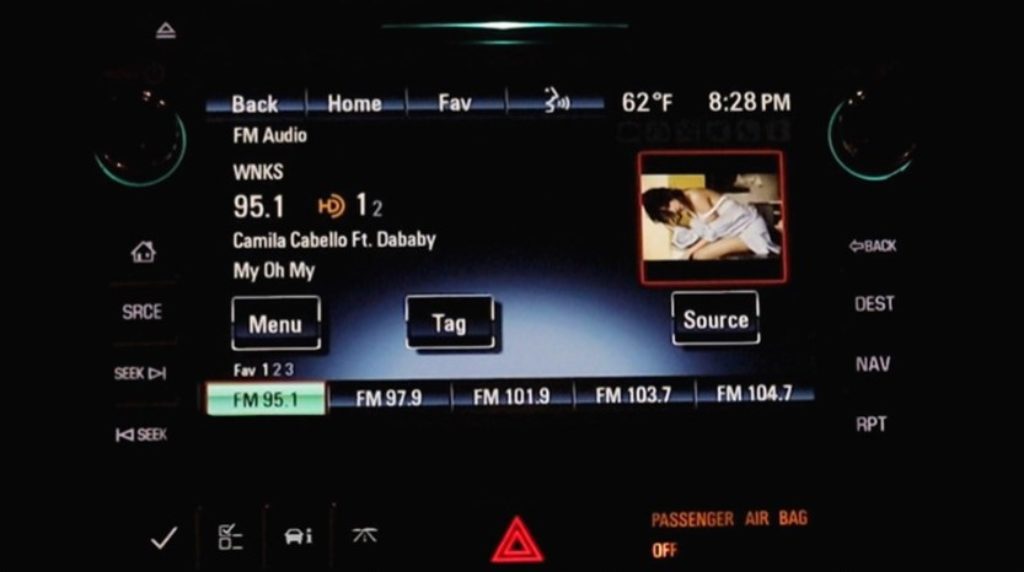

Today, the “Artist Experience” and “Advertiser Experience” display technology represents an opportunity for radio broadcasters to regain an equal footing on dashboard display.

In collaboration with Quu, more radio companies are refocusing their attention on ever-increasing screen “real estate” in cars – especially electric vehicles.

ever-increasing screen “real estate” in cars – especially electric vehicles.

As the car becomes an even more competitive environment, how radio looks in dashboards may become as important as how it sounds.

Even to this day, HD Radio conversations among broadcasters can become as contentious as opening up the phones on a talk show to talk about, say Donald Trump, guns, or abortion. Opinions run hot on all sides of the ledger. Everyone has a reason for why HD Radio never became the “next big thing” for radio during a time when the industry was looking for good news to tell Wall Street.

Come to think of it, we’re there again. And it will be interesting to see whether HD Radio and its technological tentacles can help radio broadcasters remain a part of the conversation – and the dashboard.

Meantime, what do you get for a 15 year-old?

See if she wants a radio.

This video is on Xperi’s website and might have come in handy a decade or so ago.

Originally published by Jacobs Media