When did the AI Revolution, as we may come to call it, actually start? Of course, the Artificial Intelligence technology has been around in different forms for many years, suggesting songs or learning our destinations in the car.

But the modern AI movement more likely will be dated back to the release of ChatGPT in November, 2022. For most of us, that’s when AI not only became tangible – it became accessible to all of us.

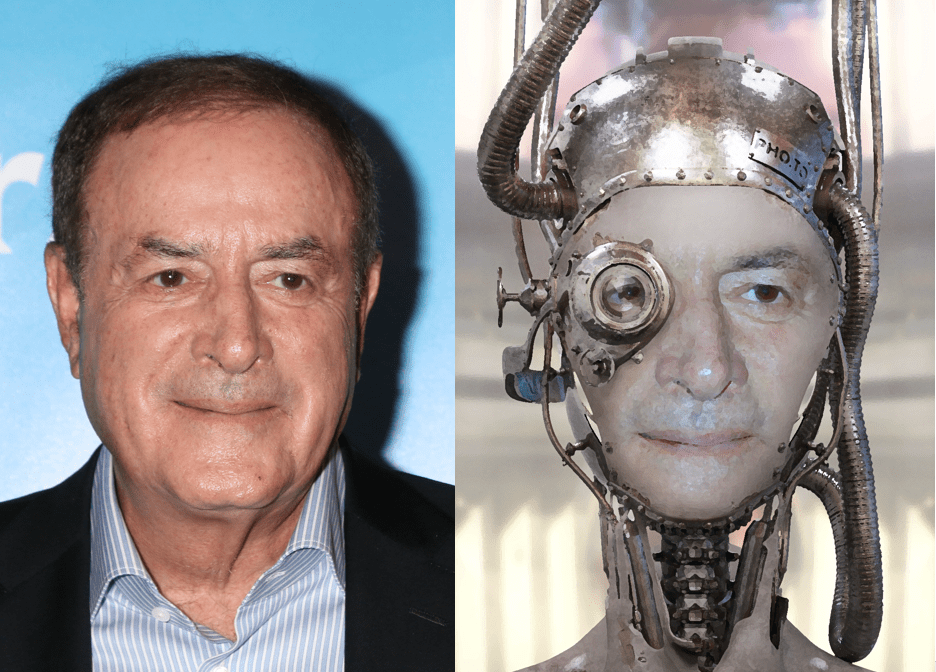

The real “AI” Ashley Elzinga

In the radio industry, the first “storm warnings” came early, wrapped up in the notion companies might replace live talent with trained bots. And soon after, Alpha unveiled “AI Ashley” in Portland, a version of DJ Ashley Elzinga, a talented voicetracker. (You can read the initial “AI Ashley” story here.)

Since then, there have been isolated examples of AI sidekicks and other mostly gimmick-type uses of AI in the air studio. The more publicized AI applications have been behind-the-scenes – AI as a prep tool (see Tracy Johnson’s Radio Content Pro), a producer of spec spots (see ENCO’s SPECai), and dozens of backend tasks most of us don’t relish anyway.

Until this month, when NBC/Peacock announced that as part of their Summer Olympics media package, the network would turn to an AI feature to personalize their coverage.

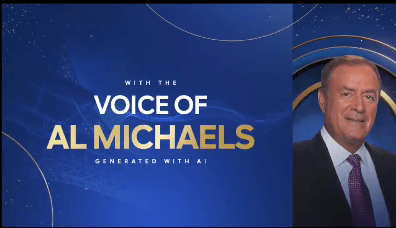

And it is all derivative of a familiar and trusted voice of just about every sports fan, Al Michaels. As the long-time anchor of Monday Night Football and other high-profile sports coverage, Michaels combines ubiquity with trust for most fans.

Last week, the network announced Michaels’ AI-generated voice will be heard on as many as 7 million customized recaps of Paris Olympics highlights starting on July 28. The Verge did the best reporting they could with little detail from NBCUniversal, including not a single word or statement from the man…er, bot…of the hour, Al Michaels himself.

The Verge report compares these AI summaries to how sports announcers’ voices are repurposed in video games, like Madden. But the difference is their AI engine will crank real-life capsules of Olympic coverage voiced by Michaels, and using the “personalized” name of the user whenever possible.

In an interesting note, these capsules will be available on supported browsers of iOS (Apple), but there’s been no detail about whether they will be able to consumed on the Android equivalent.

NBC says fans will be able to select up to three different sports of interest, as well as two different types of highlights (“Top Competition” or “Virtual & trending Moments”). The content, voiced by “AI Al,” will be delivered to your email box.

This example was included in the press release:

Before we go down the pointless rabbit hole of whether “AI Al” is a reasonable facsimile of the “real” Al Michaels, let’s instead focus on what this means to talent and their employers.

First, a team of NBCU editors will be used to vet these AI-driven capsules. This process will ostensibly be used to ensure the technology isn’t contaminated by factual “hallucinations,” causing “AI Al” to misstate a fact or simply say something erroneous or stupid.

How will this review process will work when demand is high, and hundreds of thousands of rabid Olympic fans will want to hear wrap-ups of their favorite sports or event, voiced by the artificial version of one of the all-time best sports commentators?

And will they even know they’re listening to the real voice of Al Michaels or the synthetic AI version? The demo reveals NBC is informing fans they’re using this technology to clone Michaels’ real voice (pictured below). Is this tiny screen mention enough but does anyone really care where his voice is originating from? The font is small, not unlike disclaimers in car insurance and pharma ads. Does NBC hope we don’t notice it?

Nowhere in The Verge article does it speak to the contractual arrangement between Michaels and NBC. Does the network essentially own any version (real of artificial) of his image and voice? Was an addendum added to an existing contract covering Michaels’ AI version? Is its usage approved for this particular promotion or does it apply to future uses? And does Michaels have the ability to okay the use of his artificially intelligent character for specific uses and cases?

These are questions that every talent agent in our business should be pondering, not to mention personalities and voiceover pros whose voices (and in some case, faces) are utilized in multimedia settings. How much of one’s persona should be signed away, at what cost, and under whose control? Unfortunately, not a word from Michaels about why he agreed sign his voice away, trusting the network’s producers and reviewers.

The selling out of one’s intellectual property – their IP – is no casual question. It is not dissimilar to what well-known musical icons grapple with in the decision to license their catalogues of songs.

Just last month, Queen’s music catalogue was purchased by Sony Music for the U.S. equivalent of about $1.27 billion. While the remaining members of the band will be able to tour outside the agreement, Sony now owns everything else, including a jukebox musical (that would no doubt end up on Broadway and in theaters all over the world). No doubt any of the songs in the catalogue could be (and will be) licensed to pretty much any brand willing to put up the bucks.

Just last month, Queen’s music catalogue was purchased by Sony Music for the U.S. equivalent of about $1.27 billion. While the remaining members of the band will be able to tour outside the agreement, Sony now owns everything else, including a jukebox musical (that would no doubt end up on Broadway and in theaters all over the world). No doubt any of the songs in the catalogue could be (and will be) licensed to pretty much any brand willing to put up the bucks.

In other corners of the music industry, selling one’s catalogue can be more contentious. That describes the current brouhaha between Daryl Hall and John Oates broiling over their jointly owned music library. The future of whether their music will be sold and to whom will likely end up being decided by a Nashville court.

broiling over their jointly owned music library. The future of whether their music will be sold and to whom will likely end up being decided by a Nashville court.

The use of AI to clone voice and likeness is yet the next chapter in these increasingly complicated negotiations revolving around the IP of artists – and in the case of radio, personalities. Are we nearing the point where talent will lend their voices (or endorsement) to their parent companies in exchange for financial renumeration? Who will control how and where these assets are being used?

And what about the vast population of remaining radio talent whose AI voices or their real-life endorsements aren’t as apparently valued? Will their services be as important to companies in the future?

Like so many of these AI “tentacles,” there are often more questions – ethnical and otherwise – floating around that have yet to be addressed. And to that end, AQ6 – our sixth annual survey of commercial radio air talent goes into the field in just a few days. In last year’s survey, we questioned our sample of personalities and on-air hosts about their fear of AI and its implications on radio. In this new study, we’re going to ask talent whether they’d be willing to license their IP – their voice via AI – to their employers or outside producers.

sample of personalities and on-air hosts about their fear of AI and its implications on radio. In this new study, we’re going to ask talent whether they’d be willing to license their IP – their voice via AI – to their employers or outside producers.

Our media and technology worlds continue to evolve – and in some cases – collide. We need to keep up with these changes in order to do the right thing for talent, ownership, advertisers, and of course, the audience.

As the Moody Blues reminded us in “Nights in White Satin’s” poetry at the end of this lavish song:

“But we decide which is right, and which is an illusion.”

Or do we?

Originally published by Jacobs Media