Three years may not seem like a very long time to most of us, but in radio, it can feel like a lifetime. Today’s #TBT journey back to July 2021 is a sterling example of “My, how things have changed!”

Or have they? Back then, conditions were quite a bit different. COVID was still a problem, and a return to “normal” seemed frustratingly out of reach for many – working from home, wearing masks, postponing vacations and family gatherings.

On the radio and music fronts, today’s post is a look back at the ongoing trend pointing to the strength of catalog music over the new stuff. And while Taylor Swift and a handful of others have rewritten that narrative somewhat in the ensuing years, the new music discovery landscape has been forever altered by streaming – and the phenomenon that we’re all listening to our own personal playlists and music choices.

And as the post points out, part of the appeal of music from the Classic Rock era is that common experience of hearing songs for the first time on the radio and/or thanks to friends and family who spent time playing the music for us.

Could these musically shared moments ever occur again? Or has technology as we know it continued to splinter and fragment those moments when communities of people enjoyed music together? This old post has a few ideas that might make you laugh or maybe start thinking “what if?” That was the point back then and it’s the point today. – FJ

June 2021

Radio and records veterans are only too aware of the basic trajectory of new music discovery. For eons, the labels have first identified artists who recorded albums and singles. The very best songs – the “singles” – were then released and delivered to radio stations in the appropriate format. And then their promotional machines took over. Concerts, station visits, and other marketing activity ensued.

And that is primarily how hits were made. Some songs – especially by established artists – were added on their day of release. Others required both the ears and courage of a program or music director, willing to go out on a limb to support a new song or an up-and-coming band.

First, it was surveying record stores and tracking requests to determine if a new song had a chance to crack through. Later, it was callout research that helped determine whether radio was on the right track – figuratively and literally.

But in recent years, the old model has developed stress cracks. Labels have less faith in radio. And most stations are no longer as adventuresome as they once were, especially at a time when the larger markets are reliant on meters to determine how many are listening.

And so, the labels have become more reliant on other methods of discovery – streaming services like Spotify, Apple Music, and Pandora, the channels that play new music on SiriusXM, songs featured in TikTok videos, and Shazam hits on new music consumers have the urge to identify.

You’d think that with all these new music exposure elements, the music industry would have infinitely more reliable ways of making one of their projects successful. But there is much evidence to the contrary, suggesting the further they move away from radio, their marketing methods become less reliable.

Case in point: A story in Heavy Consequence by Jon Hadusek uses the “pure album sales” metric – physical + digital sales – to make the point that rock is indeed not dead yet. Aside from K-Pop phenoms BTS (at the top of the chart), the rest of the big-sellers are Rock acts:

-

-

-

-

-

- BTS

- Beatles

- Metallica

- Queen

- Fleetwood Mac

- Pink Floyd

- AC/DC

- Nirvana

- Foo Fighters

- Led Zeppelin

-

-

-

-

As I stared at this august list of bands that can sell albums, most are in the Classic Rock department. And Hadusek reaches the same conclusion:

“(After BTS), the rest of the list is dominated by classic rock and metal bands that remain as visible and vital as ever.”

While this makes a statement about the timeless quality and resonance of music that is 30, 40, and even 50 years of age, it also says something about the ability of newer acts to break out and become the new stars of 2021.

More proof of a different kind comes from Music Business Worldwide and a story by Tim Ingham with this blaring headline:

“Over 66% of all music listening in the U.S. is now of catalog records, rather than new releases”

The previous story gives the hierarchy of albums, mostly by groups that have been around for decades. And now we learn that digital streaming – the modern way to listen to music – is dominated by catalog – i.e., older music.

Ingham reports new MRC Data shows that in the first half of this year, two-thirds (66.4%) of total consumption was, in fact, catalog (defined as having been released over 18 months after a listener presses “play”).

The trendline on this data shows a pattern. In the first six months of 2020, 63.9% of consumed music was catalog. The year before – in the pre-COVD 2019 – it was 60.8%.

Conversely, of course, consumption of new music is headed in the opposite direction.

Conversely, of course, consumption of new music is headed in the opposite direction.

And with a little voodoo math, Ingham extrapolates this trend out to 2030. If it holds, catalog music will reach 76% of listenership, compared to new music at a very puny 24% for that year in the not-so-distant future.

To veterans of radio and records, this trend seems downright counter-intuitive – except that it’s happening right before our very ears.

As the record companies devote less energy and resources on radio exposure of new music, the less current bands and their songs seem to be having impact – not just on our sales, but in our culture.

So, what is radio’s role in new music discovery in 2021 – and what should it be?

To determine how core radio listeners see it, let’s look at this year’s Techsurvey (conducted in January/February), and why core listeners still enjoy broadcast radio. We give our respondents a long list of potential attributes, and it includes “discover new music/new artists.”

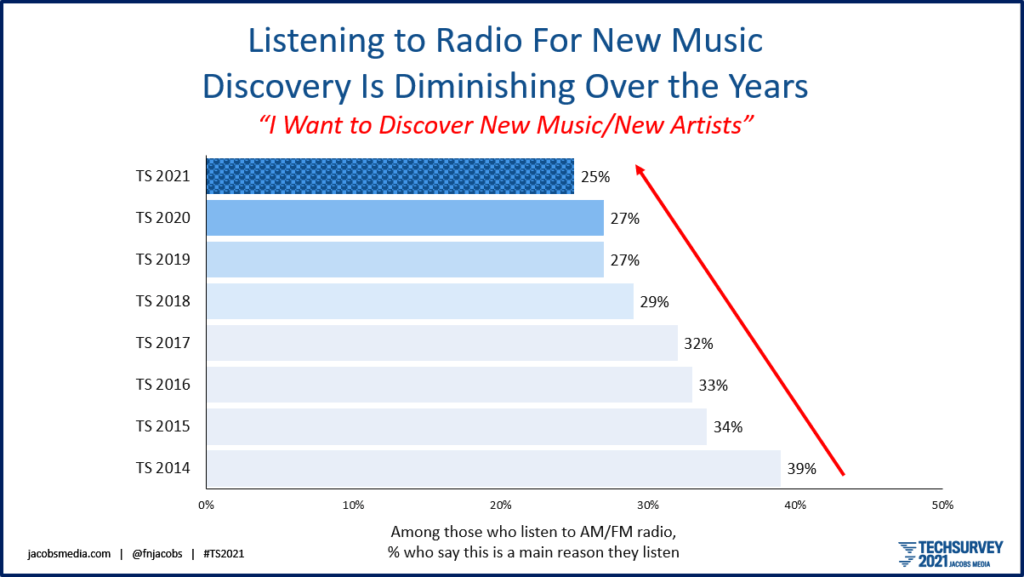

This year, nearly one in four (25%) told us new music discovery is a main driver for broadcast radio listening. But the startling finding is the eight year trend:

The chart is dramatic, reinforcing the larger trend that new music appears to be having less and less impact on our culture, and it is certainly a less impactful reason for listening to radio.

But why is that?

As consumers’ listening time is fragmented across a seemingly infinite number of audio sources, there is less collective airplay of new songs and emerging artists. Radio programmers know that frequency of a song’s exposure is a key ingredient to reach mass numbers of consumers. And the more outlets that play a song, the greater the likelihood it will become a hit.

As the Classic Rock guy, it pains me to see an opportunity for broadcast radio go untapped. But that is, in fact, the case with new music exposure on U.S. radio airwaves.

U.S. radio airwaves.

At the time Classic Rock exploded on the air and in the ratings back in the early-mid ’80s, music exposure on FM radio and MTV had been dominated by new stuff: “Hot Hits,” music videos, Michael Jackson and “Flashdance.” And that is a big part of what opened the door to a format that was 100% catalog.

And so you have to wonder if a mirror image exists with radio in America in 2021. Yes, there are stations playing new music from many different format genres, but the industry’s aversion to teen consumers is so rigid, it’s hard to imagine anything especially new or innovative breaking out in a major market geared to young people.

What if there was a station that only played new music – across genres – that was all about music discovery?

Could it move the needle on selling new music rather than catalog?

Could it recharge the types of music consumers stream and listen to over the air?

Could it get ratings? And could salespeople actually sell them?

Could it influence foreign broadcasters to actually tune in to American radio to see what’s going on – like they did in decades past?

Could it actually stimulate young people to listen to the radio – perhaps discovering it – in some cases – for the very first time?

Well, could it?

Originally published by Jacobs Media