When things get a little weird, complicated, multi-layered – OK, squirrely – I try to slow down the game. One of my little tricks is to boil down the mess and chaos into a single solution, action, problem to solve. It doesn’t always work because there is always the possibility of a multiple-alarm fire.

Today’s #TBT post is a short hop back just two years ago this month, and a post I enjoyed writing because I made it about my favorite person on the radio org chart – the PD.

At the end of the day, it’s about leadership and how just one person in an organization can make something happen. Many of your operations are cash-strapped and understaffed. That’s OK – this post was written just for you.

It’s “make a difference day” at your radio station. Here are some thought-starters. (Please add yours to the “comments” and let me know how your staff and your audience reacted to these little gems.) – FJ

March 2023

Who has the toughest job in today’s radio station?

Of course, this assumes that one person is actually only doing one job. These days, that’s not a real perceptive conclusion. Most owners have taken multitasking seriously, and consequently, many radio station employees are wearing multiple hats.

But just looking at my question, title by title, which conventional radio job is most challenging in 2023?

OK, no surprise given who’s writing this post, but I have to conclude it’s the program director. In many ways, the role has changed a great deal over the years. And in others, it’s the same job it’s always been – just exponentially more complicated and multi-layered.

Back in the day, programmers were radio gods – some of the biggest names in the business, right up there with the morning man (and it was almost always a man or two men.). PDs like Scott Shannon, Oedipus, Larry Berger, Steve Rivers, John Gehron, and so many others, were the toast of radio. The really good ones moved up the market ranks from small to medium to major, commanding more and more money – power and respect.

While some may have had the benefit of research or a consultant, they mostly ran their own starships, as my friend Tom Bender called radio stations back in the ’70s and ’80s. A single radio station typically had a 40-person staff. And it was the program director tasked with the station’s vision and execution. The sales department deferred to these influential programmers, and even general managers offered up their opinions but moved back and then let the PD make the call.

It was an uncomplicated job in many ways. Pretty much the only content that got created revolved around the over-the-air product – music, jingles, production, contests, and events. And in the top 25 markets at minimum, there were assistants, music directors, and promotions and marketing people to contribute to these creative tasks. The PD, however, was the boss of the airstaff – the style and execution of the format, airchecks, and even the look of the team.

It was an uncomplicated job in many ways. Pretty much the only content that got created revolved around the over-the-air product – music, jingles, production, contests, and events. And in the top 25 markets at minimum, there were assistants, music directors, and promotions and marketing people to contribute to these creative tasks. The PD, however, was the boss of the airstaff – the style and execution of the format, airchecks, and even the look of the team.

It was all about what went out over the airwaves. There were no secondary platforms. All that mattered was what came out of the radio speakers.

The buck stopped with the PD – and rightfully so. He was generally in control of the product. And when “the book” came out, there was only one person to congratulate or interrogate. Programmers owned their ratings, good, bad, or otherwise.

My, how that role has changed. Who actually occupies the PD’s chair is pretty much the same today as it was back then. Only about 11% of radio programmers are women. And while there’s been some growth, it’s been incremental.

As I’ve discussed here before – and at Morning Show Boot Camp when presenting our AQ studies comprised of air talent – women in radio have a much tougher climb. Given that PDs often start their careers on the air, fewer women in the air studios makes fewer female PDs a self-fulfilling prophesy.

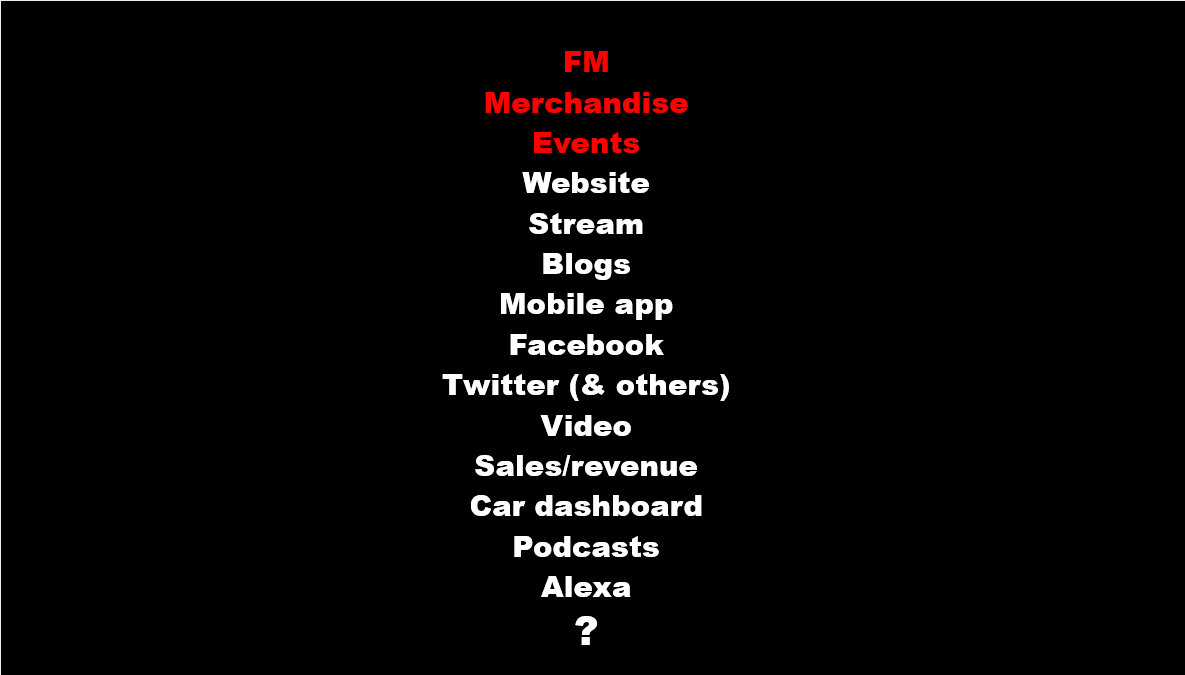

No matter the gender, the PD role has become so much more difficult. That’s because there are so many other content centers than the content on the airwaves. I made up the graphic below that illustrates many of the other content areas that contain the call letters and/or the brand. While many programmers may not have the time to play watchdog over content on these various channels, it is all content consumers experience – for better or for worse.

In red, I highlighted the basics of the PD job when I last programmed in the early ’80s. Aside from the on-air product, merch, and station events, my main focus was always on the product that was disseminated by the transmitter and the tower in the local metro.

Today, the job has expanded to a point where most PDs simply abdicate these other content centers and platforms to others, or in many cases, they may not be really supervised or managed by anyone. Eventually, unmanaged assets hurt the brand, and are often sunset or cancelled due to a lack of resources, bandwidth, or both.

Another difference? Listeners now have an efficient and often effective feedback loop with social media, platforms that can amplify any decision, especially if it proves to be unpopular. In the old days, a disgruntled listener called the station and a receptionist took a message. If someone got really hacked off, they might have the commitment to write a letter and mail it to the station. Today, reactions are instantaneous. Anything is liable to end up on social, from staff memos to clocks.

One thing that hasn’t changed is that the PD is probably the one person on the management team most tasked with the challenge of both managing up (the GM and corporate) and managing down (the airstaff and direct reports). Often, she must insulate the one group from the other in order to maintain a positive vibe. And when it comes to advertiser decisions – inventory, the appropriateness of a campaign, spot loads, sponsorships, live reads, roadblocks – the onus is on the programmer to explain why additional revenue opportunities could turn out to be problematic to the audience and the brand. In these situations, a beleaguered PD may be the only one fending off a misguided marketing idea, an unpopular place to be.

One thing that hasn’t changed is that the PD is probably the one person on the management team most tasked with the challenge of both managing up (the GM and corporate) and managing down (the airstaff and direct reports). Often, she must insulate the one group from the other in order to maintain a positive vibe. And when it comes to advertiser decisions – inventory, the appropriateness of a campaign, spot loads, sponsorships, live reads, roadblocks – the onus is on the programmer to explain why additional revenue opportunities could turn out to be problematic to the audience and the brand. In these situations, a beleaguered PD may be the only one fending off a misguided marketing idea, an unpopular place to be.

I have a huge amount of respect and empathy for today’s programmers. The job has certainly become more difficult. And the feedback I get is that many are frustrated with their ability to affect change and improvements. It is disheartening to spend a long day at a station only to walk out at night and wonder if anything actually got accomplished that day.

So, that’s the idea of this post. While it may be difficult for any number of structural or systemic reasons to make macro changes to a station, it is not at all difficult to set an important goal:

Every day, strive to do just ONE thing to make the station better.

It doesn’t have to be a world changing shift or a wildly innovative change. It can be the simplest of things that in their own small way improve something on the air, relations with a staffer, an audience connection, anything. And it doesn’t need to take long to accomplish.

air, relations with a staffer, an audience connection, anything. And it doesn’t need to take long to accomplish.

And when you’ve hit your daily goal, write it down. Journal it. And go back after every quarter to review your efforts.

Let me give you a few examples of what this might look like. The list below took almost no time to put together. And that told me there’s all sorts of room for improvement at many stations. We’re talking about those little things that can add up:

- Help a rep get a buy by offering to (or actually) going on a sales call.

- Jump on your station’s biggest social media platform and thank people for listening (or clear the phone lines in an adjacent studio if listeners still call in).

- Spend a few minutes talking to someone at the station you never interact with. How are they doing? How are the kids?

- Bring donuts, bagels, or treats in for everyone.

- Take the airstaff out to dinner (try to do it quarterly). If money is tight or you can’t get reimbursed, go to Taco Bell. It’s all about the gesture – not the burritos.

- Speak to a high school or college class in the area.

- Jump in the station van and drive around for an hour. Take in how other drivers and pedestrians react. If you have any swag, pull into a strip mall or well-traveled parking lot and give it away.

- Raise some money for a needy group, cause, or an especially unlucky person in town. If you’re a public or a Christian station, feel the joy of donating dollars for a deserving group instead of your station.

- Go into the database and call three people with birthdays today. If you get voicemail, leave a birthday greeting. If the listener answers, leave those birthday wishes, thank him or her for listening, and ask what they’d like to hear on the station.

- Sit in the parking lot for 15 minutes and do a quick audit of the FM band and your market’s metadata. Start at 88 and go all the way to 108, noting how every station looks (including yours and your cluster partners).

- Inventory your production and your promos. What’s been in too long? How’s everything rotating? Is your messaging strategic? If it’s broken or dysfunctional, fix it.

- Hop in the car and spend an hour driving around during a daypart you often don’t get a chance to listen to (probably middays). And how’s the competition sounding?

- If you’re driving a 10 year-old (or older) car, visit a local dealership and test drive something shiny and new with a modern infotainment system. Remember what it’s like to be behind the wheel of a new car.

- Make it a point to thank someone on the staff who did something positive for the station or your department.

- If you have an outside supplier – like your voice person – send him/her a $25 gift card.

- Hotline a host for doing something really well. Rinse. Repeat.

- Visit a station client, introduce yourself, and thank them for supporting the radio station.

- Record a video thanking everyone for listening and post it on your/the station’s socials.

- If some swag or promotional items come in (tickets, T-shirts), pull one or two aside to gift someone in your department station “just because.”

- Test drive your station’s mobile app. How’s it working? Is it being updated? What is it like to listen to your station on the app?

- Go into the archives and find a fantastic thing the station once did (an event, promotion, etc.). Find a way to “resurface” it on the air, the website, and/or on social.

You can undoubtedly do better than this list, because you know your station, your brand, and your community better than me.

These basic things can be very simple positives, especially if your station, cluster, or company is struggling or in the doldrums. You can make a difference at your station, in your building, in your company. And you don’t need a big budget to do it.

What’s the ONE thing you can do today to help your station? Once you get in the habit of routinely doing these basic niceties, you may find other managers following your lead. Your lists of joyous to-do’s will grow. And doing stuff like this will become a habit.

As the famous philosopher from Asbury Park, Bruce Frederick Joseph Springsteen, once said:

“From small things, big things one day come.”

Believe it. It’s true.

Originally published by Jacobs Media