One of the toughest things for radio veterans to deal with is acquiring the changing skill sets necessary to not only be successful in your career, but to make a tangible contribution to your company and even your industry. If you work for a music station, it was all about developing a set of skills revolving around research, scheduling, feature programming, presentation, and storytelling. Similarly, working for a news/talk station required the journalistic basics – interviewing, editing, presentation, and of course, balance.

But these days, a key to making an impact in the radio business may have less to do with those traditional skills, and much more to do with creating content and marketing opportunities that are uniquely different. And that’s not an easy task to master. To that end, helping your brand make a difference and find unique way to serve new customers is the new black. If it was easy, anyone could do it.

In the meantime, most radio stations and clusters are so busy doing the same old things they lose sight of how so many of their brands and shows are losing their “cume urgency.” When every day and every show is essentially the same, radio is giving up ground to other platforms and outlets, while eroding its heritage brands.

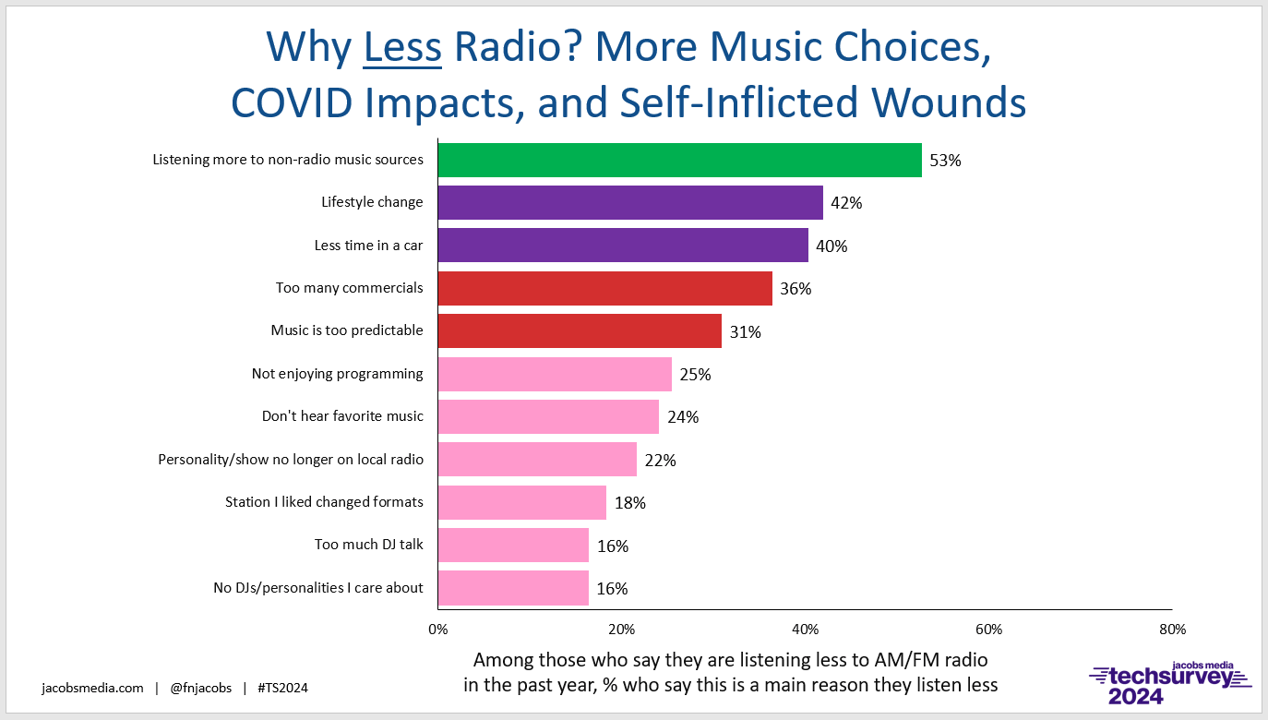

In the new Techsurvey 2024, we always spend time looking at the people who say they’re spending less time with radio year over year. The good news is that it’s only 11% of the sample. But the bad news is that 11% is coming right out of most stations’ core fan base. Because our respondents are primarily P1s, when one in ten flies the coop, you’d better find out why.

A look at the culprits reveals a predictably familiar list of external problems and self-inflicted wounds.

Sure, there’s a hierarchy here, led by a majority who point to new media options. The pandemic-era aftershocks are diminishing, but still very much in place. More than four in ten of these disaffected radio listeners are spending less time stuck in traffic and their lives have changed (moves, retirements, career change, etc.) all of which impact the routine of radio listening.

And mentioned by more than three in ten are the standard Achilles’ heels of radio – out of control spot loads and repetitive music. We might want to call these “unforced errors” because they have become sore thumbs that continually impact listening behavior.

In this mosaic of meh is a clarion call to programmers to try something different. It’s why we gravitate to unconventional approaches – Howard Stern’s interview with President Biden, playing “Dark Side of the Moon” during the eclipse, and other programming curve balls that make listeners sit up and take notice.

And along these lines are the other moves radio stations can make that aren’t your standard fare ratings and revenue go-tos. Take public radio, for example. Right now, many stations around the country – along with NPR – are struggling with “the two R’s.”

And along these lines are the other moves radio stations can make that aren’t your standard fare ratings and revenue go-tos. Take public radio, for example. Right now, many stations around the country – along with NPR – are struggling with “the two R’s.”

On news stations, those always dependable standard bearer news magazines – “Morning Edition” and “All Things Considered” – are showing wear and tear, while other programs aren’t pulling their weight in audience ratings or attracting donations during pledge drives.

Add to that most public stations are hurting from the advertising recession felt industry wide, and you’ve got a vicious cycle of underperformance.

To make matters even more challenging, the podcast strategy so many have employed has also been disappointing, leading to layoffs throughout the system. I covered this in a recent blog post, “What About Public Radio’s Muscle Memory,” earlier this month.

In the same way some stations are beginning to experiment with their fundraising models – after all, pledge drives are public radio’s equivalent to 10 minute stopsets on the commercial side of the dial – looking for a different path to success is something more stations should be considering, especially when facing a news cycle already fatiguing more and more core listeners.

In the same way some stations are beginning to experiment with their fundraising models – after all, pledge drives are public radio’s equivalent to 10 minute stopsets on the commercial side of the dial – looking for a different path to success is something more stations should be considering, especially when facing a news cycle already fatiguing more and more core listeners.

Nathan Grayson

That takes me back to a possible solution I’ve talked about before – game development. Obviously, Wordle is the poster child for this strategy. And a recent article in a newsletter called “Aftermath” by Nathan Grayson (pictured) presents the schematic for a game theory for radio that might prove to be easier than creating the next “Serial.”

(Grayson also works as a games reporter for the Washington Post).

In this edition, Grayson makes a bold headline statement that should cause all media mavens to take a pause:

“The New York Times Is Now A Game Company That Also Provides News, Based on Time Spent”

Grayson provides a thorough walk-through of how the Times’ game strategy – starting with its historically successful crossword puzzles – expanded and became a highly successful subscription model when the company made its most brilliant move: buying Wordle for a pittance.

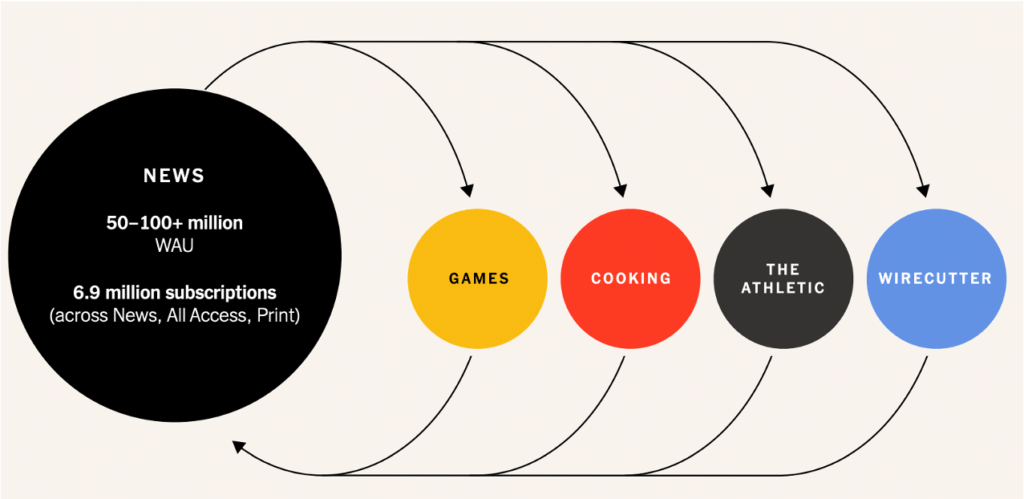

Newspaper readership – like morning radio listening – was once a dependable habit. But not anymore. As the Times discovered with its Games platform, and later its Cooking vertical, it could grow its customer and revenue bases by expanding into these adjacent but different areas.

Today, the company has amassed several “non-traditional” content avenues, all of which attract subscribers who may/may not read the newspaper.

In the case of Games, Grayson explains that it’s the antidote to a tough news cycle – just the kind we’ve meandered into now leading into an election fronted by two immensely unpopular, rapidly aging politicians.

He quotes the Times’ head of games, Jonathan Knight, “The news can be kinda lumpy, but games are a daily habit.”

Bonus: Games attract a younger audience than news stories about rising inflation and another meeting of the G7.

(New music is “lumpy,” too – an obvious message for music stations that keeping a station’s collective fingers crossed waiting for the “next big thing” in music to walk down from Mt. Belzoni isn’t a winning strategy either.)

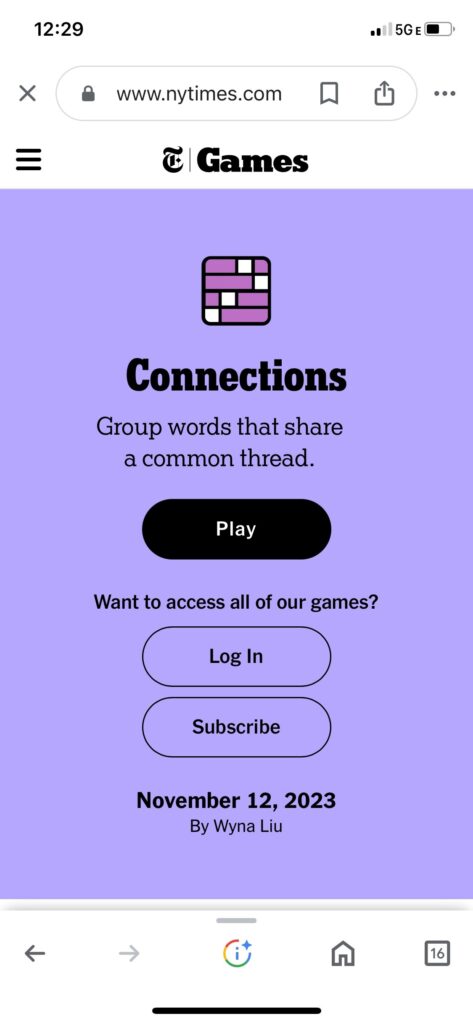

Rain or shine, stock market up or down, or your team wins last night’s battle on the diamond, court, or rink, your favorite game will always be there. After acquiring Wordle – and the “tens of millions” of new users the Times immediately began attracting with a sustainable, habit-forming game – the Times’ developed its next hit – Connections – a clever puzzle game where you create groups of four that have a common theme (the word version of radio’s “My Three Songs”).

Rain or shine, stock market up or down, or your team wins last night’s battle on the diamond, court, or rink, your favorite game will always be there. After acquiring Wordle – and the “tens of millions” of new users the Times immediately began attracting with a sustainable, habit-forming game – the Times’ developed its next hit – Connections – a clever puzzle game where you create groups of four that have a common theme (the word version of radio’s “My Three Songs”).

I dutifully play both Wordle and Connections every day – or night. Whether I read the Opinion page or check out the Business section, these quick-hitting games (I’m in and out in under 10 minutes) provides a nice mental break while also ensuring I visit the Times online. It’s a much better, scalable strategy than posting clickbait every day.

These Times games are also socially shareable, thanks to simple and familiar color-coding that allows for not-so-humble bragging on any social platform you frequent. Countless millions share their scores, challenging friends, family, and co-workers to compete as well.

I didn’t have many good options, and in the end, I was glad that through process of elimination, I solved the Wordle in 4. And how did you do? Wordle #1,043 4/6

⬜⬜⬜⬜🟨

⬜🟩🟩⬜⬜

⬜🟩🟩⬜⬜

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩— Donna Halper (@DevorahLeah) April 27, 2024

In the newspaper industry (just like in radio), the copycats are stepping up. Grayson tells us Hearst Publishing – owners of dozens of newspapers around the U.S. – bought Puzzmo, a puzzle game concept created by independent game developers. And the Washington Post has reportedly made game creation a priority as well.

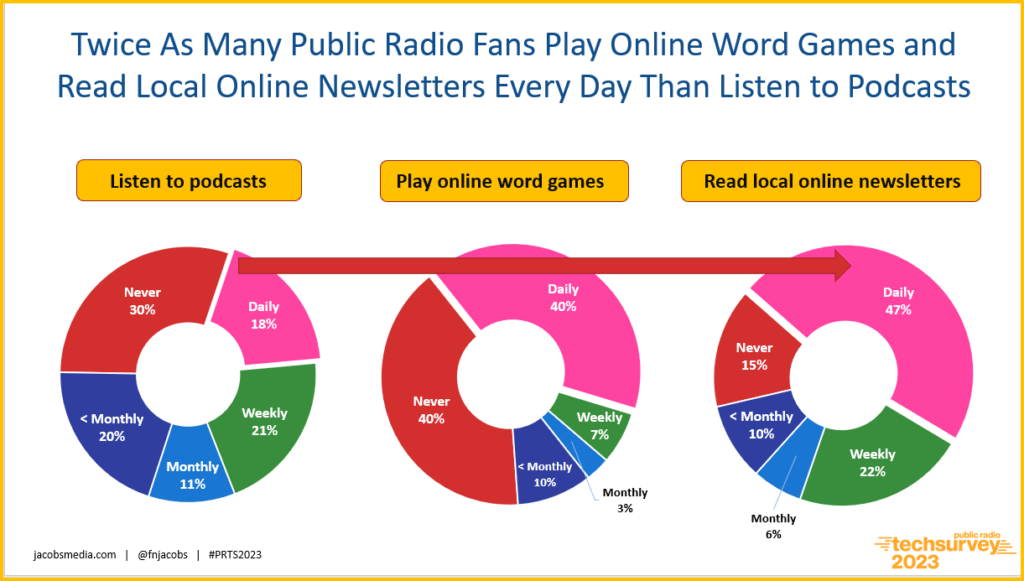

In radio, not so much. I’ve blogged about the opportunity several times in the past year, bolstered by data like the three pie charts you see below. Looking at actual usage among core public radio listeners, you can see how games (and newsletters) grossly outperform podcasts in daily usage:

Whether you’re the Times, NPR, or Z100, you’re got to fish where the digital fish are in order to grow audience.

And of course, games offer other big benefits – the chance to aggregate email addresses. Unlike podcasting or OTA or streaming listening, subscribing to a gaming platform – even if it’s free – can help a station or network digitize its audience, a key component in thriving in this highly-contested media environment.

email addresses. Unlike podcasting or OTA or streaming listening, subscribing to a gaming platform – even if it’s free – can help a station or network digitize its audience, a key component in thriving in this highly-contested media environment.

Grayson quotes his former boss, Mike Hume, who spent time playing catch-up at the Washington Post;

“You can’t predict the news. Some days it’s crazy. Some days, it’s completely a snoozefest. But you’re always going to have a crossword puzzle to play. In that way, you have these elements that are really good about building daily habits. And as a news provider, as a media company, that’s what you want: You want somebody to come and check your site every day, to make it part of their daily routine.”

For the Times, games are proving to be a steadily rising cure for “The Trump Slump,” a malady virtually every organization – including many NPR News stations – may still be suffering from.

Speaking of slumps, the other uncontrolled variable is the media advertising market. In the publication and broadcasting arenas, it has not been dependable. Hume puts a point on it:

advertising market. In the publication and broadcasting arenas, it has not been dependable. Hume puts a point on it:

“The ad market is terrible. There’s very real news fatigue. There’s tons of alternative sources for news that aren’t even news agencies. You have to find ways to generate revenue and generate audience, and games absolutely could be part of that.”

And then there’s the community piece. Puzzmo developer Zach Gage tells Grayson how games can lead to the formation of groups of listeners who invite other friends to play/join, thus expanding the web.

And then there’s the community piece. Puzzmo developer Zach Gage tells Grayson how games can lead to the formation of groups of listeners who invite other friends to play/join, thus expanding the web.

Mike Hume adds an observation about how newspapers never knew what they had with simple puzzles and games they’ve mindlessly published forever. I might make the case that radio stations with on-air games of their own fall into this same observation about missing the moment:’

“I think (newspapers) never fully understood how much potential crossword puzzles and other games have in terms of generating audience and retaining that audience through prolonged engagement.”

Grayson paints the picture of how many publishing organizations are jumping on this bandwagon, trying to create their own platforms and strategies.

Is this happening anywhere in radio….yet? It’s doubtful. And yet, the potential might be just as great.

Will Shortz

Consider NPR already has the New York Times’ “puzzle master” Will Shortz (pictured) on staff, hosting a weekend segment for years. (We’d have to check to see if he has an enforceable “non-compete,” wouldn’t we?)

NPR might have another advantage – a wildly successful game show. “Wait, Wait…Don’t Tell Me!” has anchored weekend programming on hundreds of public radio stations for more than a quarter century.

Peter Sagal

Maybe brainy, wise-cracking host Peter Sagal (pictured) would be up for a “side hustle” for a game that public radio fans would rapidly adopt. Brand extension for “Wait, Wait…” might be just the thing NPR needs to jumpstart internal creativity.

So, here’s my quiz question:

Which is these is easiest to create and monetize?

a. A hot new, evergreen podcast?

b. A hot new weekday radio program?

c. A not new habit-forming game?

And the answer?

It depends.

But given where everyone else in radio is fishing these days, we’d be likelier to generate more action in a pond with fewer competitors.

Josh Wardle via LinkedIn

Maybe Wordle creator, Josh Wardle (seriously) has another game in him. Is it harder to find great podcast producers, showrunners, or game developers? We won’t know until we try.

The Times is well aware that for Game to continue on as a sustainable profit center, the organization will need to create new, compelling puzzles.

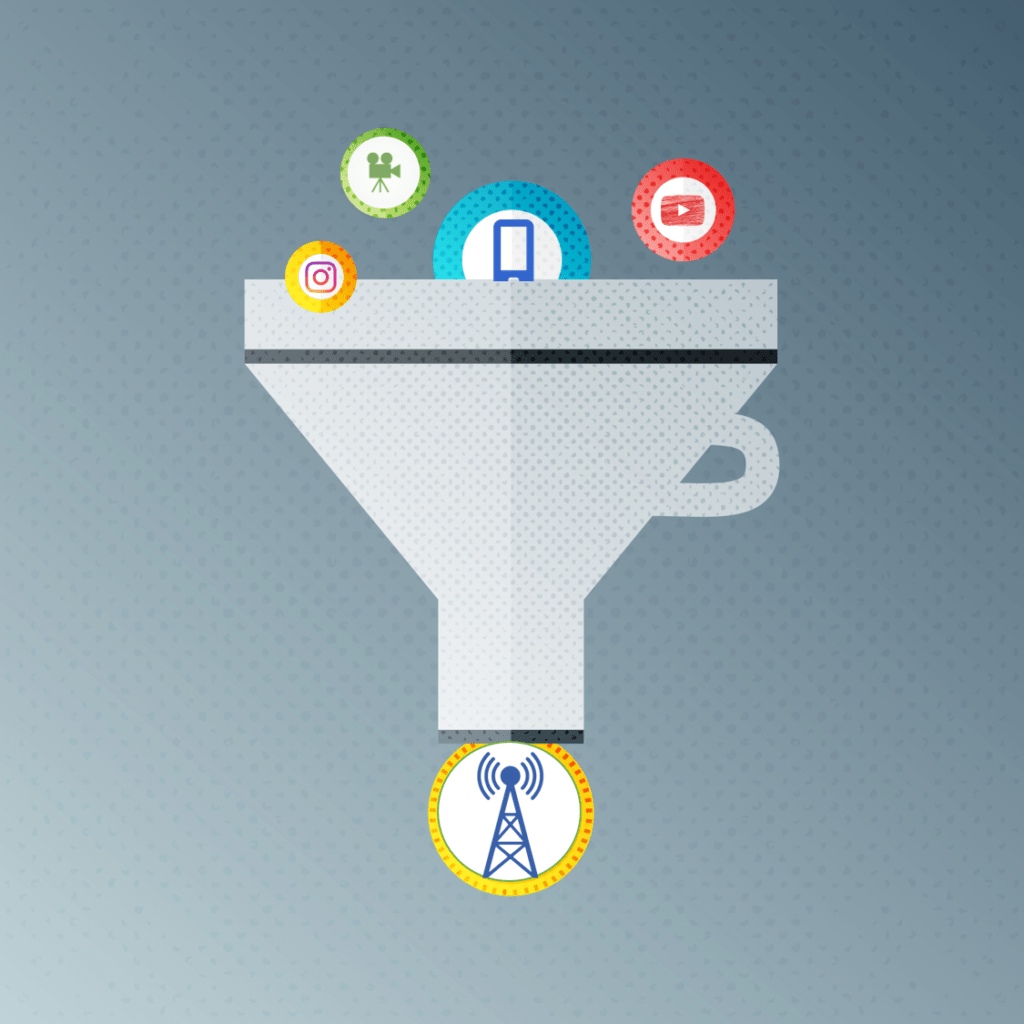

Grayson quotes Zoe Bell who’s the executive producer of the Games division at NYT:

“We are trying to make the next Wordle, but we’re doing it in a very measured way. We have this philosophy about game design where you start with a wide funnel with all the ideas and you make decisions about whether or not you’re gonna work with a few of them. And then you get smaller, and you prototype a few, and then you share a couple of those with the wider audience and see what sticks. We’re not trying to invest too much in an idea that might not take off. Hopefully that produces a hit game, and it did with Connections. I think that’s sort of proving that strategy.”

measured way. We have this philosophy about game design where you start with a wide funnel with all the ideas and you make decisions about whether or not you’re gonna work with a few of them. And then you get smaller, and you prototype a few, and then you share a couple of those with the wider audience and see what sticks. We’re not trying to invest too much in an idea that might not take off. Hopefully that produces a hit game, and it did with Connections. I think that’s sort of proving that strategy.”

To that end, the Times recently beta-released a new “word search” type game called “Strands.” Not a fan. And that’s OK, because you’re not going to love them or be addicted to them all. But a new game can easily tested, refined, adapted, and evaluated. If there’s a fail, you move on and create another.

called “Strands.” Not a fan. And that’s OK, because you’re not going to love them or be addicted to them all. But a new game can easily tested, refined, adapted, and evaluated. If there’s a fail, you move on and create another.

Is there a “there there” for a games strategy for a radio organization – commercial, public, Christian networks and/or stations?

Yogi Berra

Given how many on-air benchmarks are quiz/trivia based, you’d have a tough time dismissing this game theory out of hand.

As the great philosopher, Lawrence Berra, is famous for saying:

“The game isn’t over until it’s over.”

Originally published by Jacobs Media