In the pre-Internet world, it was a fairly simple task to categorize music and connect it to discreet audience tastes. Everything worked pretty chronologically. The era of songs and albums you grew up with became – for the most part – “the music of your life,” to invoke an old radio phrase.

But as today’s #ThrowbackThursday blog post illustrates, all musical bets are off. The simple calculus of music and one’s life journey has been altered by the hardware and software that help us track music, build playlists, and control our music experience. Add to that the disparate way consumers – especially young ones – are exposed to music: on TV, in movies, in video games, and while watching football games.

That data I stumbled across when this post was originally published very likely still hold up today. It’s filled with eye- (and ear-) opening data that may make you rethink your time-honored philosophies about music decades and audience targeting.

What year did “Mr. Bright Eyes” come out? Or “Running Up That Hill?” If you first heard them while watching your favorite team play football or while watching a popular series on Netflix, that petty much dashes the notion of music synching up with years of our lives. If your first exposure to Kate Bush was a couple years back while enjoying “Stranger Things,” she’s a new artist to you.

And does it even matter to anyone outside of radio who’s coding these songs?

So what’s your favorite decade of music? – FJ

June 2021

Research budgets are at a premium in radio this year, thanks in no small part to the ravages of the pandemic. After a cataclysmic year like the one we’ve just experienced, this is the opportune time to take the audience’s temperature – so to speak – to learn about how they’ve come through 2020, as well as the impact of a year when habits and routines were severely disrupted.

But if there’s no cash on hand or a music test or perceptual study in the planning stages, I may have the next best thing for you. Aside from some of the essentially free research out there – our Techsurveys, Edison’s Infinite Dial studies, and Nielsen’s general trends and overviews, new research from YouGov may be just what you’re looking for – especially if you’re in need of some accurate insights about changing musical tastes.

They’ve just wrapped up an extensive study of Americans that ranges from the Silent Generation (seniors born between 1928-1945) to Gen Z (born in 2000 or later).

The study is focused on music tastes, specifically the decade of music people prefer most. It’s a big sample – north of 17,500 respondents – and it’s fresh. The field work took place earlier this month.

Musical decades are a frequent topic in virtually every conversation I have with clients. And they’re also the subject of much debate. Your favorite 10-year period of music says a lot about you and your tastes.

Some contend the music you grew up with is essentially your playlist for life. Others believe that music tastes, especially in recent years, have been warped by media, technology, and other variables, making it highly possible you have a preference for music that came out years before you were born.

Now, thanks to YouGov America, the answers are taking shape. Data journalist Jamie Ballard published the piece last week: “Americans say the 1970s and 1980s were the best music decades.” And while her headline speaks volumes about where mass appeal tastes are centered, the devil – as always – is in the details. In this case, the data.

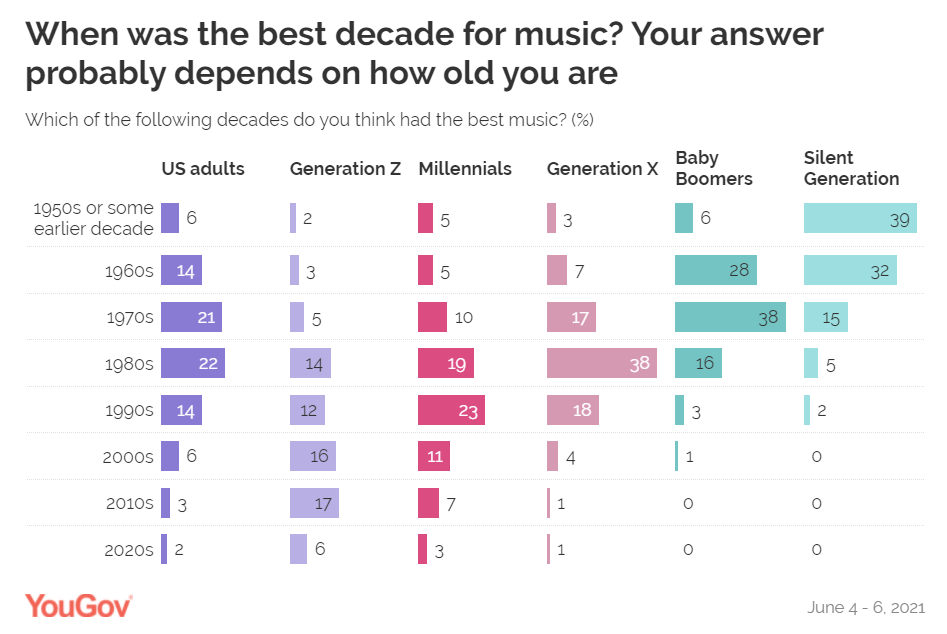

Here’s the study’s key chart – a cornucopia of research findings that should settle many old arguments about music tastes, while igniting several new ones:

As the headline suggests, your age – more specifically, when you were born and your formative musical years – dictates your go-to decade. But only up to a point. It holds for older generations, but not so much for their younger kids and grandkids.

Predictably, members of the Silent Generation heavily favor oldies from the ’50s, Boomers rally around the ’70s (the Classic Rock years), while Gen Xers have a definite lean toward the ’80s (those MTV-era hits). Chronologically, this fits Ballard’s premise.

And there’s strong generational agreement about their decades of preference. Close to 40% of each generation gravitate to their favorite 10-year musical period. That’s a big part of the reason music radio formats work so well and are dependable. Music tastes tend to be demographically predictable, falling into those neat generational columns.

And there’s strong generational agreement about their decades of preference. Close to 40% of each generation gravitate to their favorite 10-year musical period. That’s a big part of the reason music radio formats work so well and are dependable. Music tastes tend to be demographically predictable, falling into those neat generational columns.

But it’s the Millennials where it all breaks down. While the 1990s are their preferred decade, there’s much less consensus for music that ranged from Grunge to Alanis Morissette to Limp Bizkit to Hip-Hop. In fact, less than one in four express love for the ’90s, followed by the ’80s (19%), and then the ’00s (only 11%).

Passion and a decade focus all but deteriorate for Gen Zs. Not surprisingly, their favorite decade is music from the 2010s – their version of “currents” -– but only with 17%. Nearly as many of these teens opt for the ’80s and ’90s as they do the music of today.

Most of you reading this are not in your teens. But if you think back to those special years, they were a time of music discovery and unabashed passion. Chances are, you were tuned into music of your day, buying it on whatever format was popular, as well as attending concerts.

passion. Chances are, you were tuned into music of your day, buying it on whatever format was popular, as well as attending concerts.

But that love affair with “the music you grew up with” when you were an impressionable teenager is a non-starter for both Gens Y and Z. It doesn’t mean today’s kids don’t enjoy new music because many do. But the chart explains why we see teens wearing AC/DC shirts. Or all those twentysomethings who show up at Elton John concerts. Or the droves of kids watching Bohemian Rhapsody again and again.

Why is this happening and why do the two younger generations show a much different pattern than their elders?

Many believe that today’s music pales in comparison to the greatest hits of the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. Jamie Ballard even quotes the prophetic words of Bob Seger in the lead paragraph of her story:

“Today’s music ain’t got the same soul – I like that old time rock n’ roll.”

I’m not buying it.

For the second half of the last century, it made sense that large coalitions of fans formed around an artist or even a genre of music. That’s because everyone was listening to the same music on the same source at the same time:

Radio

In the 2000s, that began to change, starting with the iPod explosion. MP3 players had been around before Steve Jobs created an entirely new market for aggregating, selling, organizing, and playing music. The Apple iPod became a “must have” device, and it spawned a new way to listen to music – from lots of different genres.

In the 2000s, that began to change, starting with the iPod explosion. MP3 players had been around before Steve Jobs created an entirely new market for aggregating, selling, organizing, and playing music. The Apple iPod became a “must have” device, and it spawned a new way to listen to music – from lots of different genres.

Then came streaming services, notably Pandora and then Spotify. Technology changed the ways in which consumers were being exposed to new music. And while broadcast radio is still a dominant source for music, myriad other outlets have splintered a once monolithic market. YouTube, TikTok, video games, and of course, streaming platforms have all changed the way music is exposed. Today’s kids still love music, but they’re all listening to a different mix.

The fact that just as many Gen Zs prefer music from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, than newer releases that are 2010 and later says it all. As a child of the ’60s myself, I cannot imagine taking a survey in 1968, and selecting the 1940s or even the 1950s as my favorite decade.

But that’s where we are today.

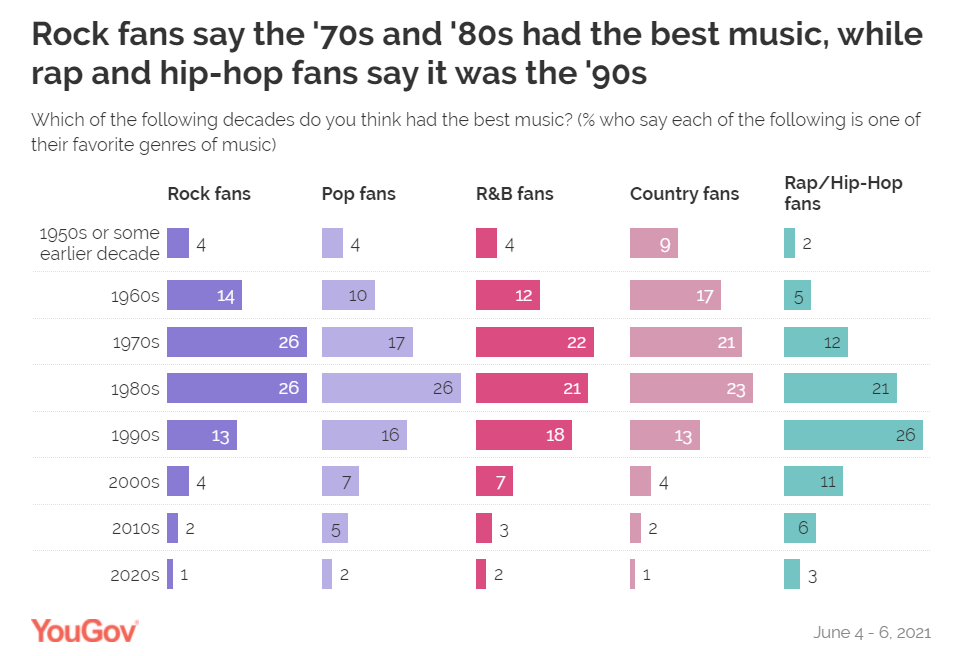

It gets even more eye-opening when you look at YouGov’s data by format or genre:

For Rock fans (and there is no delineation for Classic or Mainstream Rock), it’s all about the ’70s and ’80s. Interestingly, the ’60s edge out the ’90s.

Those who identify as Pop partisans (another vague descriptor) present a true radio programming conundrum. Only 7% opt for music from the 2010s and later. Their favorite decades are the ’70s, ‘800s, and ’90s.

Country fans present a true puzzle. And I would recommend not showing this chart at the next CRS get-together. For a format that leans heavily on newer music, only one in five Country P1s opt for songs from 2000 and newer. Meantime, it’s the ’90s and then the ’80s where you see strong agreement.

And for Rap/Hip-Hop, the YouGov number indicate those “throwback” radio stations are onto something. A solid plurality point to the ’90s as the epicenter of their musical tastes.

I realize many radio programming mavens will scoff at this data, saying the ratings, their music research, and their perceptual studies reveal very different results. I would counter that with the fact that when radio broadcasters consider those under 25 and those over 54 as non-targets, the industry is missing not only a large segment of the audience, but billions of dollars of spending power as well.

I realize many radio programming mavens will scoff at this data, saying the ratings, their music research, and their perceptual studies reveal very different results. I would counter that with the fact that when radio broadcasters consider those under 25 and those over 54 as non-targets, the industry is missing not only a large segment of the audience, but billions of dollars of spending power as well.

To walk away from Gen Z, the Silent Generation, and the bulk of Baby Boomers raises all sorts of questions about the state of the business. YouGov counted all those people

So which is it? Is the music you were exposed to when you were 12 or 13 years-old the songs and artists you’ll still love when you become a senior citizen? Or has today’s technology warped the ways in which teens are exposed to new music, thus ending the traditional generational appeal patterns?

My experience with Classic Rock and music research suggests that both theories may be true – at the same time. Among Silents, Boomers, and Xers, it is about the songs (and albums) that echoed through their high school gyms and dorm rooms that became permanent parts of their musical DNA.

But for Millennials, Zs, and the generations to come, all generational music bets are off. Pop culture, videos, movies, social media, and games have become powerful music exposers. And it’s not just new releases or up-and-coming artists.

How else do you explain that phenomenon last summer when Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams” started charting again after its release four decades ago because it was the soundtrack in that TikTok video that went super-viral?

@420doggface208

People started drinking Ocean Spray Cranberry Juice again, too. And they didn’t run a single ad on the radio.

Radio programmers will have to work harder (sad, but true) to keep up with the changes wrought by digital media and non-linear exposure to music.

Originally published by Jacobs Media