How’s your station sounding these days? Plus or minus, there’s a good chance it doesn’t sound architecturally much different than it sounded back in 2014. Or 2004. Or even 1994 – if you’ve been around that long in the same format. Perhaps some people have come and gone, the music is different (if you’re playing new stuff). But structurally, the essential sound probably isn’t a whole lot different than it’s always been.

And that’s a good thing, right? Radio is a game of consistency and habit. As a programmer, the goal is usually to create a comfortable, familiar environment to become part of an audience’s routine, an essential link in their daily habit structure – especially Monday through Fridays when things tend to play out pretty much the same way.

But if you talk to some of the most successful people in business about your game plan, they might question the essence of what you’re doing. The co-CEO of Netflix, Ted Sarandos (pictured below), is one of those guys. And he’s got the receipts to prove it.

The Hollywood Reporter was on hand during a recent keynote Sarandos made to the the Royal Television Society’s London Convention. Among other things, he talked about Netflix’s two biggest competitors – not Amazon Prime, Hulu, or Disney+.

the the Royal Television Society’s London Convention. Among other things, he talked about Netflix’s two biggest competitors – not Amazon Prime, Hulu, or Disney+.

It turns out two of the biggest stumbling blocks the company has faced are video piracy and Netflix’s own DVD business.

Maybe the first doesn’t surprise you, but the second one will. It was Netflix’s success with mailing DVDs to us in those signature red envelopes that almost led to the company’s demise. That’s because most CEOs wouldn’t have let the company’s massively successful video streaming model come to light. Most would have hung onto the DVD business for dear life, ceding video streaming to another player – like Amazon, Apple, or even Spotify.

But the Netflix core team were disciples of former Apple visionary Steve Jobs who spent prime chunks of his career cannibalizing his own business. Remember that Jobs put Apple’s wildly successful iPod franchise on the line when he introduced us to the iPhone. And soon after, he challenged iPhone’s dominance when Apple unveiled the iPad.

At each turn, Jobs wasn’t afraid to advance his company’s trajectory by disrupting Apple’s biggest divisions with something new, different, better. Sarandos summed it up this way: “If you ever find yourself protecting the business (you’re in), you’re pretty much dead…We’ve got to constantly challenge ourselves to break (the business) and move our business forward on behalf of our consumers.”

“Break the business.”

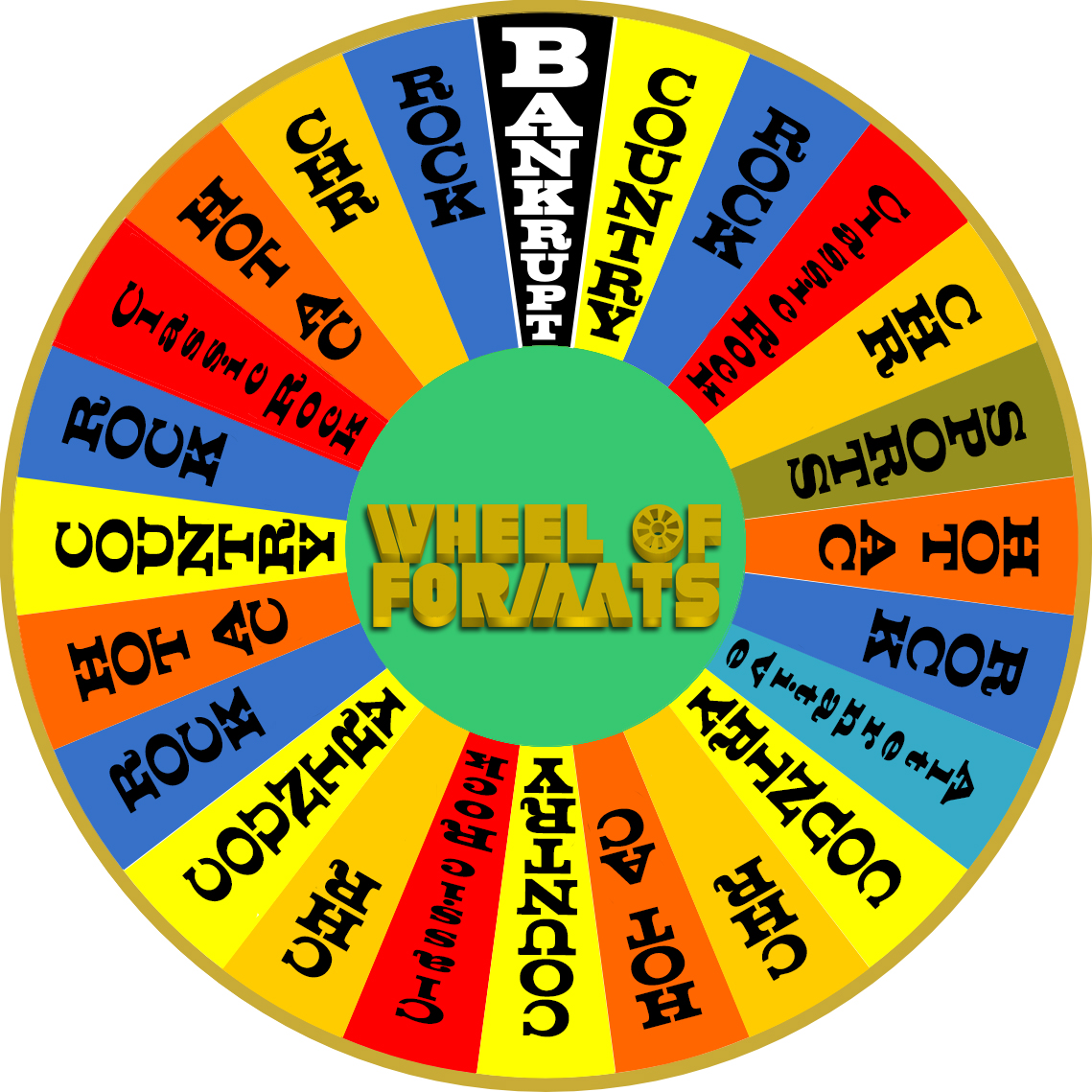

Imagine if Steve Jobs owned a radio company made up of a couple hundred stations in its portfolio. Would they all sound the same? That is, would every one adopt tried and true formats like Hot AC, Classic Rock, Sports Talk, and Alternative – the “Wheel of Formats” that thousands of radio stations all over the country do a version of?

its portfolio. Would they all sound the same? That is, would every one adopt tried and true formats like Hot AC, Classic Rock, Sports Talk, and Alternative – the “Wheel of Formats” that thousands of radio stations all over the country do a version of?

Or would at least a handful of those stations have been committed to becoming sandboxes, incubators – grand and not-so-grand experiments to try something different – a format literally outside of the industry’s rigid box?

Was consolidation supposed to be merely a tool designed to achieve financial dominance? Shouldn’t it also have been the green light to use at least a few of those tokens on the board to do things perhaps a little avant-garde or experimental – to see what’s around the corner, to figure out what’s next?

It’s all part of a “fan first” philosophy at Netflix, an acknowledgment that the company’s clientele don’t all have the same tastes. As Sarandos implored the assembled attendees in London, “Put the audience first.” That means, how can Netflix look at its company mission through the lens of fans, “not critics or media execs.”

Other key reminders: “Success is more art than science.” In media companies at least, that’s tantamount to embracing the reality that algorithms cannot do it all. Human programmers have to make the calls. And that’s going to mean taking a shot on a show like The Crown, something different than CSI or America’s Got Talent. In a hierarchy like this, there will be flops. But that’s the way media companies become successful.

I’ve spent considerable time with rank-and-file broadcasters over the summer, especially at state broadcaster association gatherings. At these conventions, galas, and awards dinners, you spend time with everyone – grizzled veterans, young entrants into our business, big market pros, and mom & pop owners, many of whom are second and third generation family broadcasters.

Despite the diversity of these attendees, however, the driving question is the same:

Are we going to be OK?

And the answer, of course, is nuanced. It isn’t simple, because big, hairy audacious questions can never be answered with a simple “yes” or “no” response. It’s more complicated than that.

Fortunately, there’s a schematic for how to make change happen. It’s an essay in Medium from this past summer. Called “Act different” by Mike Maples, Jr. that describes how you get there from here.

Like Ted Sarandos, Maples channels the swashbuckling Steve Jobs who didn’t just welcome radical unorthodox thinking in Apple – he encouraged and nurtured it.

“Break the business.”

I love this quote, because it reminds me of some of the great programmers, air talents, and content creators over the years who didn’t rely on templates, algorithms, or formulas to design and execute their programming.

There was a time in radio where we sought out these types of people. They were mercurial, difficult to manage, and they rarely filled out their HR forms on a timely basis.

But they created new format and innovations, they found talent in odd places, and they questioned everything. As Maples notes, they have the ability to distinguish “between the world that is and the world that can be.”

He reminds us of the need for leadership that “acts differently, thrives on confrontation, challenging the status quo and fostering high expectations.”

So, when broadcasters from all walks of radio life ask me “the question:”

Are we going to be OK?

I hesitate because I firmly believe that the longer radio continues to do pretty much everything the same way, the best we can expect is to tread water and live to fight another day.

If that’s the expectation, we have a shot. Radio is no longer a great business, but it still is a good one. And it might be able to hold onto that status for a while.

But to not just to survive but to thrive, this industry is going to have to throw the ball down the field. Who knows? We may not complete the pass. We might even throw an interception. In essence, anything can happen.

And that means we might even score a touchdown.

Let’s put some points up on the board.

“Break the business.”

Originally published by Jacobs Media