Every industry loves cliches, axioms, and tenets that help to easily describe its reality. For radio, the mantra since the rise of the Internet in the early 90s has revolved around the notion that radio people are innovative, resilient, and spry. We survived television in the 1950s and MTV in the 1980s. This Internet thing is a challenge to be sure, but don’t count radio out.

That’s obviously a reassuring balm that has made radio broadcasters feel better for the last thirty or so years. But is it true? Does one event long ago portend the same outcome years later? What was different about the attack of television in post-World War II America – and radio’s response – that was analogous to the world of online media that’s been with us now for more than three decades, spawning a tsunami of tech breakthroughs, including the iPod, smartphones, social media, podcasts, streaming audio and video, and now AI?

Not a whole lot actually. It’s not until you go back and study radio’s survival strategy when television first became ubiquitous in living rooms, rec rooms, and dens – first in black and white, and later in color – that shook radio’s long-held position as the in-home entertainment and information medium. We smile at those sepia-toned photos of multiple generations of families gathered around a radio, listening to variety shows, radio dramas, comedies, and the voices of American presidents.

shook radio’s long-held position as the in-home entertainment and information medium. We smile at those sepia-toned photos of multiple generations of families gathered around a radio, listening to variety shows, radio dramas, comedies, and the voices of American presidents.

Most people in radio today don’t know this history during the momentous period when television disrupted everything. I found a succinct summary on a MacMillan higher education site, a resource for teachers. It’s a good read.

I believe that if radio is to wriggle its way out of its current conundrum, understanding how the medium coped with its previous existential challenge is important

Radio’s ability to reinvent itself in the 1950s was actually a 20+ year process. When TV’s began showing up in people’s homes, the pain point was less about the devices and much more about content. The programming/talent drain radio suffered at that time at the hands of TV was devastating. As MacMillan notes, “Remarkably, the arrival of television in the 1950s marked the only time in media history when a new medium stole virtually every national programming and advertising strategy from an older medium. Television snatched radio’s advertisers, program genres, major celebrities, and large evening audiences.”

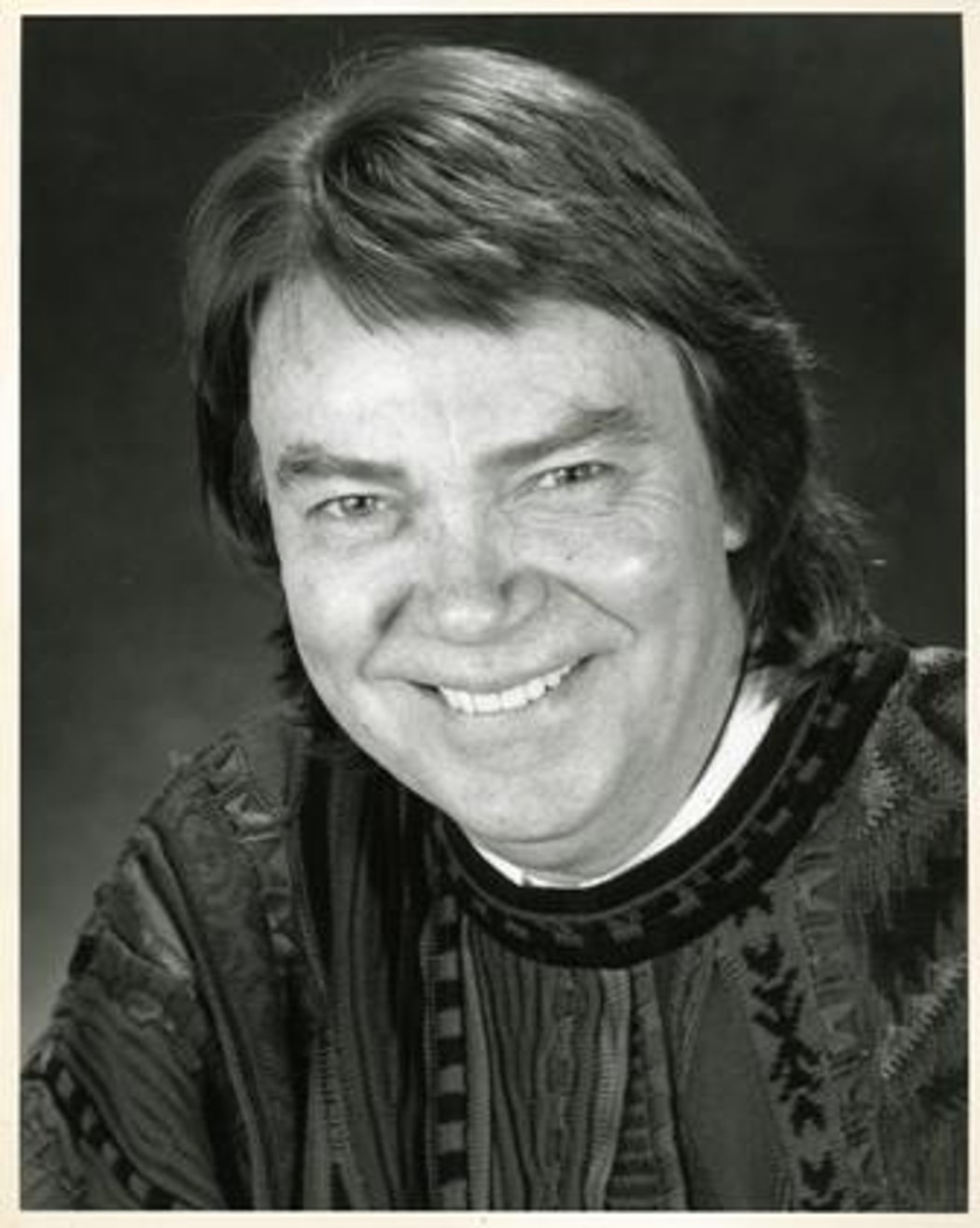

“The Jack Benny Show”

It is hard to imagine what those old radio broadcasters must have endured. Think about every mega-personality and hit show leaving the radio airwaves to instantly become fixtures on the hot new medium – television. Stars and their hit shows like George Burns and Gracie Allen, “The Lone Ranger,” and Jack Benny (pictured) led the exodus. It’s no wonder why everyone in America ran out to buy TVs. And that was the final crowning blow, of course: all those radios in millions of living rooms being replaced by television sets.

So, we think what radio has been enduring over the last decade or so has been disruptive? In many ways, it pales in comparison to what those radio pioneers had to cope with during that post-war America media boom.

So how did radio not just bounce back, but completely pivot its business model?

The first element may have been technical. As the MacMillan piece explains, the transistor was developed by Bell Labs in the late 1940s. It was the technology that allowed radio to unshackle itself from electrical outlets to become portable.

The first element may have been technical. As the MacMillan piece explains, the transistor was developed by Bell Labs in the late 1940s. It was the technology that allowed radio to unshackle itself from electrical outlets to become portable.

Transistor radios weren’t large, expensive, or complicated, allowing consumers of all ages to take radio with them wherever they went. Unlike radio devices tethered to big vacuum tubes, transistors were tiny, allowing for radios to fit in pockets and purses. For radio broadcasters, it was a game-changer. While those lost the living room to TV, they gained portability, the ability to go anywhere.

Of course, the car radio had been around for decades, still giving radio the exclusive in cars, an advantage it still enjoys today, even with the encroachment of streaming media, satellite radio, podcasts, etc. As we know, radio is still #1 in the dashboard.

And finally, there was also the emergence of FM radio in the 1960s, thanks in part to the FCC who opened up more spectrum for stations, FM’s high quality audio, and the vision of programming pioneers who innovated compelling format radio.

This last piece – the content – is at the heart of radio’s makeover in the 50s and 60s, exploding in the 70s when FM surpassed AM in listening and revenue. Without it, all the above technology would have helped radio broadcasters, but it wouldn’t have saved them.

Bill Drake via Radio Info

Radio patriarchs like Todd Storz, Gordon McLendon, and Bill Drake (with Gene Chenault) were the geniuses who envisioned the coming of format radio – essentially the same playbook radio broadcasters have run ever since.

Many credit Storz with the invention of Top 40 radio he perfected at the radio company he and his father created starting in Omaha. McClendon – also with his father – created a radio empire. He also had a hand in developing radio play-by-play starting with baseball, and creating what would become the all-news and beautiful music formats. And Drake’s “Boss Radio” became the signature sound of Top 40 radio during the era, introducing audience research and demographics to the strategic conversation.

All three of these visionaries owned stations themselves, an interesting and important distinction. They had the opportunity to experiment with their own properties, and they all brought important innovations to the changing medium that captured the hearts, minds…and ears of Americans, especially the legions of young people who became the core of the Baby Boom.

“FM” Soundtrack | MCA Records

While many radio broadcasters may have been caught off guard by FM (the next disruption), most of the formats that had become popular on the AM airwaves made their way to the high quality audio provided by frequency modulation. As Steely Dan summed it up in the title song of the 1978 movie soundtrack, “FM,” these stations promised “no static at all,” a stereophonic advantage over all those AM giants.

In essence, FM was “the next big thing” for radio, an innovation that occurred within the legacy medium – not coming from the outside like streaming or social media has during the Internet Age.

With FM, the technical and programming revolution came from within. Radio broadcasters were able to control the disruption – after all, they owned the heritage AMs while learning what was going on down the hall at their FM stations. As revenue shifted from one band to the other, they were in position to reap the financial benefits.

So, can we conclude radio’s reinvention in the 50s paved the way for the medium to similarly survive the storm spawned by the Internet over the past three decades? After all, if past is prologue, doesn’t it stand to reason radio broadcasters will somehow find a way to reimagine its next iteration?

With a pedigree in innovation, radio broadcasters had the chops to handle the Internet tsunami in the same ways Drake, Storz, McLendon and so many other masterminded the TV invention to create a style of radio that would make it bigger, better, and more profitable than before.

But as we sadly know, it hasn’t happened. Radio broadcasters miscalculated in the 90s, with many writing off the Internet as something different and ultimately non-competitive. And with the passage of Telecommunication Act of 1996, the pathway toward station and market restructuring seemed ready-made for radio to reach a new pinnacle of success and domination.

But it hasn’t worked out that way. Radio broadcasters have generally done little content creation of significance in the new digital ecosphere. Nor have they innovated their existing sound pre- and post-Internet. Radio broadcasters today are generally running the same formats today as they were 30 years ago. Amazingly, radio’s reach has generally held up as consumers continue to tune-in. But digital streaming has become the conduit and radio broadcasters have been cast with playing defense.

Why has there been so little evolution and innovation? Why have broadcasters missed the moment, unlike those aforementioned radio swashbucklers of the 1950s and 1960s who inarguably helped save radio?

Why has there been so little evolution and innovation? Why have broadcasters missed the moment, unlike those aforementioned radio swashbucklers of the 1950s and 1960s who inarguably helped save radio?

As we watch the fortunes of so many commercial radio companies falter as demand on commercial radio inventory is tepid, what are the reasons for the medium’s sputtering? And on the public radio side, stations throughout the country are engaged in painful layoffs, replacing organizational leaders, and redefining their digital content strategies.

But to what end? Are the next set of decisions going to lead to different – or better – outcomes than so many of the failed moves of the past?

Circumstances are different today than when Bill Drake – born Phillip Yarbrough – began to experiment with less DJ talk, hyper rotations on hit songs, and programming innovations like “20 20 News” to become the soundtrack of America during his heyday.

Clearly, the landscape is more crowded with technology, deep pocketed tech companies, and the expansion of media outlets and the gadgetry that delivers their content to us.

But this is all the more reason the decisions made during the second half of this year and through 2030 are more rational, strategic, and sound than the ones that have gotten us to this place.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the decisions companies make to green light new content and project initiatives or to instead ride it out and wait to see what happens.

There needs to be a better, more rational, studied process in place that frames these decisions so that even the most creative people in our midst have a structure for making optimal calls.

That’s tomorrow’s blog post. And I hope you’ll read it and engage.

Originally published by Jacobs Media