As media proliferate all across the landscape, more and more platforms and brands are sputtering, watching their business models underperforming. Revenue shortages are impacting media throughout the spectrum, triggering layoffs, tumult, and hand-wringing.

Sometimes those of us in radio internalize our challenges, concluding the problem must be us. While radio has its systemic issues (as my online trolls continually remind me), the fact is, broadcasters do not have the market cornered on red ink.

It is not unusual for mega-media brands to show signs of profound distress. My media savvy friend, Bob Ottaway, pointed out to me that Sunday’s New York Times “Book Review” section contained just two actual ads this past weekend, the rest of its avails used by promo for other company content.

The examples abound, but unfortunately, the solutions are slow in coming. Some examples?

Axios, publishers of local market newsletters recently purchased by Cox, announced a serious round of layoffs last week, amounting to about 10% of its workforce. But that bad news was overshadowed by the company’s CEO, Jim VandeHei, suggesting the entire media space is experiencing across-the-board disruption. In an internal memo, VandeHei issued a tough explanation for Axios’ poor performance:

“We’re making some difficult changes to adapt fast to a rapidly changing media landscape. Why it matters: We’re eliminating about 50 positions to get ahead of tectonic shifts in the media, technology, and reader needs/habits.”

Then there’s Paramount Global. The LA Times reported yesterday the media giant will take a $6 billion write-down – a sure sign its traditional TV model is in trouble. In addition, Parmount’s terminations impact a whopping 15% of its global staff as it tries to piece together its crumbling once-iconic cable channels: Comedy Central, MTV, Vh1, CMT, and Nickelodeon.

traditional TV model is in trouble. In addition, Parmount’s terminations impact a whopping 15% of its global staff as it tries to piece together its crumbling once-iconic cable channels: Comedy Central, MTV, Vh1, CMT, and Nickelodeon.

You may recall the Paramount braintrust, in an obvious but weird cost-cutting move, deep-sixed the MTV website back in June along with all its archives. Variety reported this amounted to two decades full of historic content published on MTV.News.com.

Let’s not forget the venerable CNN. Last month, the troubled cable news network announced job cuts amounting to 100 positions, or nearly 3% of its global workforce as it rolled out plans for a “one newsroom” strategy. Deadline reported the new plan mashes up “linear and digital newsgathering,” apparently amounting to the same journalists producing content for the cable channel’s assets as well as its digital outlets.

Let’s not forget the venerable CNN. Last month, the troubled cable news network announced job cuts amounting to 100 positions, or nearly 3% of its global workforce as it rolled out plans for a “one newsroom” strategy. Deadline reported the new plan mashes up “linear and digital newsgathering,” apparently amounting to the same journalists producing content for the cable channel’s assets as well as its digital outlets.

I could go on. But to spare you on a Friday, perhaps these news nuggets – or pieces of coal – put some of the recent radio layoffs into some perspective.

The fly in this ointment, however, is the difficulty of cutting a company’s way to success. CEOs can talk about “right-sizing” their organization, but the translation is the same: staff is cut because the company’s business model isn’t working.

organization, but the translation is the same: staff is cut because the company’s business model isn’t working.

The problems media companies are enduring now don’t strike me as a one-off event, due to a recession, weather emergencies, or even a global pandemic – circumstances that resolve themselves over time.

Will today’s dilemma simply play out after the election, after the first of the year, or at some other point in time? Or are we experiencing something bigger and more existential than that. The fact both commercial and public radio are facing similar dire straits suggests problems that are sadly more universal.

So, is the model broken?

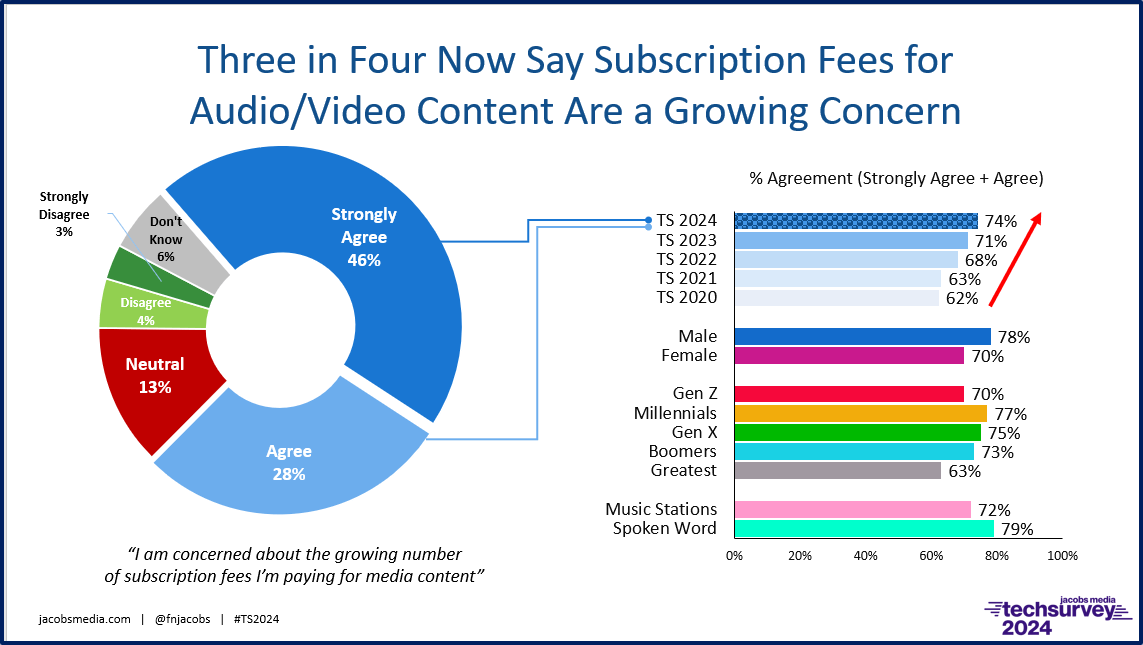

There are some indicators the “pay” aspect of media is showing serious signs of rust. I’ve pointed to the pushback against content subscription fees, the highest (or lowest) we’ve seen since including the question in our Techsurveys:

When three out of four respondents rage on how about much they’re shelling out every month for paid content, it’s a problem.

Why has the aggregation of all those content subscriptions reached the “code red” stage with so many consumers since COVID? Here’s a theory: In the throes of COVID, we were willing to pay pretty much anything to entertain ourselves and our loved ones during a period when going out was deemed to be downright dangerous. And thanks to lockdowns, we certainly weren’t spending money on discretionary entertainment: movies, concerts, sporting events, museums, bars and clubs, and our other favorite pastimes.

So another few bucks a month for Disney+ or Hulu was no big deal in the big scheme of things in the dark days of 2020. After all, these were small indulgences in the big picture of our lives.

But media companies began to believe our tastes in entertainment and our willingness to pay through the nose for it was a permanent condition. Moving forward, the average family unit would endlessly continue to sign up for more paid content services in order to indulge its entertainment and information needs.

E xcept that a couple years now beyond COVID, many consumers have come to their senses, drawing the line at signing up for yet another paid content service, whether it’s music or video streaming, satellite radio, or anything else with a monthly fee tacked onto it.

xcept that a couple years now beyond COVID, many consumers have come to their senses, drawing the line at signing up for yet another paid content service, whether it’s music or video streaming, satellite radio, or anything else with a monthly fee tacked onto it.

But what’s the alternative for those who refuse to tack on yet another paid service on top of their already bloated bill? Commercials, of course. But those of us in radio know all too well why this model is a slippery slope waiting to happen.

After all, look what’s happened to us over the years.

But what if unlike radio, other media brands had the discipline to actually limit the minutes they devote each hour paying the bills? What if they committed to keeping their commercial loads under control? A perfect example is Netflix. Two years ago, they were prescient enough to see the writing on the wall. Realizing they were missing huge chunks of the population who weren’t thrilled about the concept of paying $15 a month for the privilege to stream the platform, Netflix came up with a considerably lower priced tier with limited numbers of commercials.

Is it working? Last month, Marketing Dive noted the Netflix ad-supported platform grew its ranks by 34% in the second quarter with a minimum of 40 million monthly active users globally. That’s a pretty attractive “cume” for this bargain streaming tour, and Netflix is bringing in new sales management to cash in on this rush of viewers.

minimum of 40 million monthly active users globally. That’s a pretty attractive “cume” for this bargain streaming tour, and Netflix is bringing in new sales management to cash in on this rush of viewers.

According to the story, Netflix is taking its time, growing this initiative, expected to reach “critical ad subscriber scale” by next year. Advertiser demand is already growing – finally, an opportunity to reap the benefits of the Netflix brand.

And Marketing Dive says the competition is fierce, thanks in no small part Amazon’s addition of ads to their Prime Video channel early this year. And both channels are investing heavily into live pro sports broadcasts to lock in advertisers and viewers.

But then there are FAST channels gaining ground and favor among more and more consumers. The compelling acronym stands for “free ad-supported television,” and it’s a compelling concept. As NBC News reporter Rob Wile reported last month, the main players Freevee (owned by Amazon), Pluto TV (part of the Paramount portfolio), and Tubi (under the Fox umbrella), the Roku Channel and Xumo, co-owned by Comcast.

But then there are FAST channels gaining ground and favor among more and more consumers. The compelling acronym stands for “free ad-supported television,” and it’s a compelling concept. As NBC News reporter Rob Wile reported last month, the main players Freevee (owned by Amazon), Pluto TV (part of the Paramount portfolio), and Tubi (under the Fox umbrella), the Roku Channel and Xumo, co-owned by Comcast.

All told, these FAST channels have already blown past a 4% slice of the TV viewing pie, and Goldman Sachs projects 15% annual growth every year until 2027. Here’s the pecking order from May, slices of the nearly 39% share of viewers who watch video streaming services:

As the NBC story points out, while some viewers of these FAST channels are “cord cutters” – the millions who stopped paying for pay TV – many more may be “cord nevers” – folks who never paid for television content in the first place. These consumers simply do not wait to fork over their hard-earned money for any television. They’ll put up with a few commercials in order to achieve their video nirvana – free TV.

But much of this information about who specifically is watching FAST channels, accurate information is a rare, leaving it up to analysts to speculate about the audience groups currently rallying behind this ad-supported content. As journalist Wile says it comes down to this:

“What (FAST channel) viewers do have in common no matter their background…is a desire to pay nothing for entertainment.”

Ross Compton with Macquarie U.S. Equity Research keeps it even simpler:

“You really can’t beat free.”

Isn’t that precisely the mindset broadcast radio should be embracing? Meanwhile Spotify keeps upping its subscription fee, already instituting hikes twice this year. As of early June, Spotify for individuals is up to about $12, while their “duo” package is just shy of $17.

And then there’s SiriusXM, increasingly frustrated by their inability to grow their subscriber base. Looking at the Netflix model, the satcaster earlier this week unveiled their own ad-supported tier for no fee.

Obviously, this is a radical departure from SXM’s legacy subscriber-driven platform. Radio Ink reported that no matter how you look at the in-car battlefield, satellite lags far behind traditional radio listening. SiriusXM, however, performs much better in luxury brands, such as Mercedes-Benz and Audio, as well as in newer vehicles.

Inside Radio says there are other hoops for drivers to jump through. While SXM CEO Jennifer Witz says the new plan is all about “repositioning our business for the future,” the story goes onto say the free service is only available to owners of vehicles with the company’s 360L receivers. Additionally, eligibility is limited to those whose free trials runs out and can only be activated by one vehicle per customer.

But it’s a start. While the company acknowledges it will take time to amp up the platform’s commercial options for advertisers, you can see that’s where they’re headed. SiriusXM needs to jumpstart its user base, while cashing in on inventory sales.

Will it work? Can a radical move to offer a “free” version of satellite radio actually be a game-changer for SXM.

We can all speculate about the wisdom of this risky move by SiriusXM, but like the growth of FAST channels, it attempts to cash in on the notion of not paying cash for any media content.

And it begs the question why the legacy platform offering free information and entertainment – for more than a century – cannot leverage itself to be especially in-sync with changing consumer demands.

Clearly, part of the reason is that radio broadcasters have never even attempted to own what is an increasingly attractive position in the media marketing landscape.

But maybe the other barrier is that AM and FM radio’s commercial loads have become so bloated and unlistenable that whatever benefit the broadcast model might offer as a free service to millions of Americans is negated by excess.

Yes, radio IS free, but the price consumers pay twice an hour – usually in bowtie-positioned stopsets – cannot effectively compete against the myriad of streaming competitors.

Yes, radio IS free, but the price consumers pay twice an hour – usually in bowtie-positioned stopsets – cannot effectively compete against the myriad of streaming competitors.

Radio has “great bones.” Millions and millions grew up listening and have warm, even nostalgic feelings about the radio they grew up with. And radio is still the easiest option to listen to in most cars.

As we watch all these other channels and brands boldly experiment with their models to move the needle, isn’t it time for radio broadcasters to explore these same possibilities with its own heritage platform?

Or is it once again a case of “We’ll be right back after we pay the bills.”

Originally published by Jacobs Media