In recent years, I’ve run into a lot of people from the tech world who proudly describe themselves as “serial entrepreneurs.” And I’ve never known whether to interpret that as a good thing…or a bad thing.

Does it mean they’ve have started up one successful company after another? Or is it more the case they launched companies that never managed to succeed, due to the typical reasons: a lack of capital, bad timing (the pandemic, the recession, etc.), unanticipated competition, the wrong people, irrational exuberance, or maybe just maybe it wasn’t a great idea to start with.

I’ve been fortunate. I’ve started up two companies in my career, both based on pretty good initial ideas. Jacobs Media was hatched on my dining room table in 1983, propelled by the birth of the Classic Rock radio format. Our mobile app company, jacapps, got its auspicious start in the company storeroom in 2008. About 100 days after Apple opened its now-famous App Store, jacapps was founded on the premise that broadcast radio had lost its portability when the Walkman became obsolete. Our theory was that streaming apps on smartphones could re-revolutionize radio, restoring its ability to “go anywhere.”

dining room table in 1983, propelled by the birth of the Classic Rock radio format. Our mobile app company, jacapps, got its auspicious start in the company storeroom in 2008. About 100 days after Apple opened its now-famous App Store, jacapps was founded on the premise that broadcast radio had lost its portability when the Walkman became obsolete. Our theory was that streaming apps on smartphones could re-revolutionize radio, restoring its ability to “go anywhere.”

In both cases, there was no business plan, slick PowerPoint deck, adequate funding, or venture capital. Both companies have evolved, each a bit different than when they started. But somehow, they endure, and that’s also in spite of the fact that while I hold two degrees, I never took a single business class.

I’m not proud of that. In fact, it has occurred to me on many occasions over the years how helpful it might have been to have actually had some training in business operations, budgeting, forecasting, and yes, personnel management.

It was especially true early in my career when I went to work for ABC Radio, first at WRIF in Detroit, and later for the company’s Owned FM Stations in New York. In each case, a basic understanding of how organization charts are created and why might have come in handy.

While you will often hear me sing the praises of ABC Radio, a truly fun company to work for back in the 1970s, there was one thing about how their station staffs were configured that would eventually make me crazy. I was actually able to change it at WRIF.

While you will often hear me sing the praises of ABC Radio, a truly fun company to work for back in the 1970s, there was one thing about how their station staffs were configured that would eventually make me crazy. I was actually able to change it at WRIF.

Back then, promotion directors had a great deal of clout. They controlled, in some cases, seven figure budgets. Most of their attention was spent on the content sides of their stations. Believe it or not, working with the sales department was a secondary responsibility.

But then there were the promotion/marketing directors. Each was on the same line on ABC Radio’s station org chart as the program director, both reporting directly to the general manager. As a result, the PD and promotion director collaborated as equals, but also worked separately from one another. Programmers rarely shared intricate plans in and around the station’s sound with their marketing equal. And promotion directors worked on ad campaigns and other marketing materials on their own, sharing these plans with the PD, but also having the final call on how promotional dollars were apportioned and spent.

It made me nuts. Because when a less than stellar rating book happened, it was the PD being pelted with all the “What happened?” questions, while the marketing director was off planning the next campaign. Over time, I openly campaigned to have promotions report to programming for the good of all involved, not to mention the health and welfare of the Mothership.

That is most certainly the way it has come to be in most commercial radio situations in the years that have followed. The PD is in charge of “the product” – that includes how it sounds, how it looks, and how it is perceived and used by the audience. And that’s as it should be. The buck stops at the PD’s office, like the “showrunner” in Hollywood who has to account for how well consumers enjoyed and engaged with a piece of content, whether it’s a TV sitcom, a “romcom” movie, or a country radio station.

Over the years, the program director’s responsibilities and purview have expanded, in-synch with how technology has expanded the landscape. When I programmed WRIF, I was responsible for the on-air sound (and the ratings it garnered) as well as station events, contests, and other connected content. Today – at least in theory – the PD should be overseeing all that, PLUS the website’s content and how it looks, metadata in the car dashboard, the social media footprint and messaging, the mobile app, and anything else with the call letters on it that comes into contact with the audience.

landscape. When I programmed WRIF, I was responsible for the on-air sound (and the ratings it garnered) as well as station events, contests, and other connected content. Today – at least in theory – the PD should be overseeing all that, PLUS the website’s content and how it looks, metadata in the car dashboard, the social media footprint and messaging, the mobile app, and anything else with the call letters on it that comes into contact with the audience.

It doesn’t always cleanly work out this way, of course. And in today’s environment where there are simply fewer station employees to begin with, the program director is often tasked with performing these other functions themselves. These days, commercial radio PDs typically are also on the air, while many often oversee other brands in the building and/or in the company.

In public radio, it is typically a much different world. These days, I often think about how radio differs, especially commercial versus public. Over the past several decades, public radio has excelled, especially in the content realm. It has generally made better use of network programming, while tending to provide solid coverage of the local terrain.

But now that may be changing. Public radio’s organizational DNA and legacy job roles and responsibilities may now be harming its ability to adapt and even pivot to changing demands, not just from listeners, but also from station “ownership” (a nonprofit or university) and boards of directors.

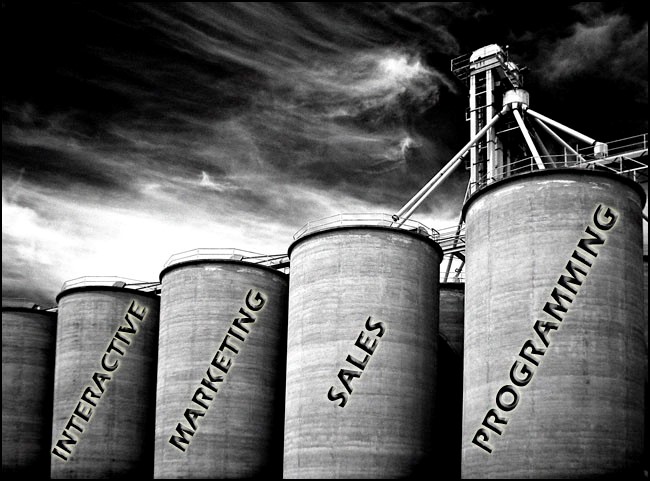

In public radio, the silos can be downright rigid and ultimately maddening. In the case of news/talk stations, there’s a news department, of course, often running independent from “programming.” Then there’s something called “development” – a combination of sales (those low-key advertiser “credits” and sponsor mentions) along with fundraising.

In public radio, the silos can be downright rigid and ultimately maddening. In the case of news/talk stations, there’s a news department, of course, often running independent from “programming.” Then there’s something called “development” – a combination of sales (those low-key advertiser “credits” and sponsor mentions) along with fundraising.

There may also be a head of content, in some cases carrying the title of Chief Content Officer. While this person may be in charge of any content the station produces, on and off air, they are not the program director. In fact, many content positions don’t require prior programming experience.

That’s because there’s frequently a “program director” position on the org chart. But unlike their commercial counterparts, most of the managers holding the position of PD in public radio have a different job. They don’t typically have many direct reports, much less the authority or responsibility to totally shape their station’s sound. In many cases, the news department doesn’t report to the program director (there’s a separate news director). Nor does the head of “development,” the department overseeing sales and fundraising.

So, who exactly is programming public radio stations? And what do they do?

Who is the person in the organization responsible for the overall vision and sound? Or is this often a responsibility shared across several departments?

In an increasingly competitive environment, brand focus becomes a critical factor in how listeners, advertisers, and donors perceive a station.

That’s where tomorrow’s conversation is headed as we tackle the question, who is in charge at public radio stations?

To read Part 2 of this post, click here.

Public Radio Techsurvey is now out of the field. In just a few weeks, it will be ready for presentation to its stakeholder stations, and later the entire industry. We will keep you updated on presentation dates.

Originally published by Jacobs Media